Let us probe the silent places, let us seek what luck betide us;

Let us journey to a lonely land I know.

There’s a whisper on the night–wind, there’s a star agleam to guide us.

And the Wild is calling, calling – Let us go.

– Service

It will be convenient to pick up the thread of our story upon the point of the arrival of the Aurora in Hobart, after her long voyage from London during the latter part of the year 1911.

Captain Davis had written from Cape Town stating that he expected to reach Hobart on November 4. In company with Mr CC Eitel, secretary of the Expedition, I proceeded to Hobart, arriving on November 2.

Early in the morning of November 4 the Harbour Board received news that a wooden vessel, barquentine–rigged, with a crow’s–nest on the mainmast, was steaming up the D’Entrecasteaux Channel. This left no doubt as to her identity and so, later in the day, we joined Mr Martelli, the assistant harbour–master, and proceeded down the river, meeting the Aurora below the quarantine ground.

We heard that they had had a very rough passage after leaving the Cape. This was expected, for several liners, travelling by the same route, and arriving in Australian waters a few days before, had reported exceptionally heavy weather.

Before the ship had reached Queen’s Wharf, the berth generously provided by the Harbour Board, the Greenland dogs were transferred to the quarantine ground, and with them went Dr Mertz and Lieutenant Ninnis, who gave up all their time during the stay in Hobart to the care of those important animals. A feeling of relief spread over the whole ship’s company as the last dog passed over the side, for travelling with a deck cargo of dogs is not the most enviable thing from a sailor’s point of view. Especially is this the case in a sailing–vessel where room is limited, and consequently dogs and ropes are mixed indiscriminately.

Evening was just coming on when we reached the wharf, and, as we ranged alongside, the Premier, Sir Elliot Lewis, came on board and bade us welcome to Tasmania.

Captain Davis had much to tell, for more than four months had elapsed since my departure from London, when he had been left in charge of the ship and of the final arrangements.

At the docks there had been delays and difficulties in the execution of the necessary alterations to the ship, in consequence of strikes and the Coronation festivities. It was so urgent to reach Australia in time for the ensuing Antarctic summer, that the recaulking of the decks and other improvements were postponed, to be executed on the voyage or upon arrival in Australia.

Captain Davis seized the earliest possible opportunity of departure, and the Aurora dropped down the Thames at midnight on July 27, 1911. As she threaded her way through the crowded traffic by the dim light of a thousand flickering flames gleaming through the foggy atmosphere, the dogs entered a protest peculiar to their ‘husky” kind. After a short preliminary excursion through a considerable range of the scale, they picked up a note apparently suitable to all and settled down to many hours of incessant and monotonous howling, as is the custom of these dogs when the fit takes them. It was quite evident that they were not looking forward to another sea voyage. The pandemonium made it all but impossible to hear the orders given for working the ship, and a collision was narrowly averted. During those rare lulls, when the dogs’ repertoire temporarily gave out, innumerable sailors on neighbouring craft, wakened from their sleep, made the most of such opportunities to hurl imprecations in a thoroughly nautical fashion upon the ship, her officers, and each and every one of the crew.

On the way to Cardiff, where a full supply of coal was to be shipped, a gale was encountered, and much water came on board, resulting in damage to the stores. Some water leaked into the living quarters and, on the whole, several very uncomfortable days were spent. Such inconvenience at the outset undoubtedly did good, for many of the crew, evidently not prepared for emergency conditions, left at Cardiff. The scratch crew with which the Aurora journeyed to Hobart composed for the most part of replacements made at Cardiff, resulted in some permanent appointments of unexpected value to the Expedition.

At Cardiff the coal strike caused delay, but eventually some five hundred tons of the Crown Fuel Company’s briquettes were got on board, and a final leave taken of English shores on August 4.

Cape Town, the only intermediate port of call, was reached on September 24, after a comparatively rapid and uneventful voyage. A couple of days sufficed to load coal, water and fresh provisions, and the course was then laid for Hobart.

Rough weather soon intervened, and Lieutenant Ninnis and Dr Mertz, who travelled out by the Aurora in charge of the sledging–dogs, had their time fully occupied, for the wet conditions began to tell on their charges.

On leaving London there were forty–nine of these Greenland, Esquimaux sledging–dogs of which the purchase and selection had been made through the offices of the Danish Geographical Society. From Greenland they were taken to Copenhagen, and from thence transhipped to London, where Messrs. Spratt took charge of them at their dog–farm until the date of departure. During the voyage they were fed on the finest dog–cakes, but they undoubtedly felt the need of fresh meat and fish to withstand the cold and wet. In the rough weather of the latter part of the voyage water broke continually over the deck, so lowering their vitality that a number died from seizures, not properly understood at the time. In each case death was sudden, and preceded by similar symptoms. An apparently healthy dog would drop down in a fit, dying in a few minutes, or during another fit within a few days. Epidemics, accompanied by similar symptoms, are said to be common amongst these dogs in the Arctic regions, but no explanation is given as to the nature of the disease. During a later stage of the Expedition, when nearing Antarctica, several more of the dogs were similarly stricken. These were examined by Drs McLean and Jones, and the results of post–mortems showed that in one case death was due to gangrenous appendicitis, in two others to acute gastritis and colitis.

The dog first affected caused some consternation amongst the crew, for, after being prostrated on the deck by a fit, it rose and rushed about snapping to right and left. The cry of ‘mad dog” was raised. Not many seconds had elapsed before all the deck hands were safely in the rigging, displaying more than ordinary agility in the act. At short intervals, other men, roused from watch below appeared at the fo’c’sle companion–way. To these the situation at first appeared comic, and called forth jeers upon their faint–hearted shipmates. The next moment, on the dog dashing into view, they found a common cause with their fellows and sprang aloft. Ere many minutes had elapsed the entire crew were in the rigging, much to the amusement of the officers. By this time the dog had disappeared beneath the fo’c’sle head, and Mertz and Ninnis entered, intending to dispatch it. A shot was fired and word passed that the deed was done: thereupon the crew descended, pressing forward to share in the laurels. Then it was that Ninnis, in the uncertain light, spying a dog of similar markings wedged in between some barrels, was filled with doubt and called out to Mertz that he had shot the wrong dog. In a flash the crew had once more climbed to safety. It was some time after the confirmation of the first execution that they could be prevailed upon to descend.

Several litters of puppies were born on the voyage, but all except one succumbed to the hardships of the passage.

The voyage from Cardiff to Hobart occupied eighty–eight days.

The date of departure south was fixed for 4 pm of Saturday, December 2, and a truly appalling amount of work had to be done before then.

Most of the staff had been preparing themselves for special duties; in this the Expedition was assisted by many friends.

A complete, detailed acknowledgment of all the kind help received would occupy much space. We must needs pass on with the assurance that our best thanks are extended to one and all.

Throughout the month of November, the staff continued to arrive in contingents at Hobart, immediately busying themselves in their own departments, and in sorting over the many thousands of packages in the great Queen’s Wharf shed. Wild was placed in charge, and all entered heartily into the work. The exertion of it was just what was wanted to make us fit, and prepared for the sudden and arduous work of discharging cargo at the various bases. It also gave the opportunity of personally gauging certain qualities of the men, which are not usually evoked by a university curriculum.

Some five thousand two hundred packages were in the shed, to be sorted over and checked. The requirements of three Antarctic bases, and one at Macquarie Island were being provided for, and consequently the most careful supervision was necessary to prevent mistakes, especially as the omission of a single article might fundamentally affect the work of a whole party. To assist in discriminating the impedimenta, coloured bands were painted round the packages, distinctive of the various bases.

It had been arranged that, wherever possible, everything should be packed in cases of a handy size, to facilitate unloading and transportation; each about fifty to seventy pounds in weight.

In addition to other distinguishing marks, every package bore a different number, and the detailed contents were listed in a schedule for reference.

Concurrently with the progress of this work, the ship was again overhauled, repairs effected, and many deficiencies made good. The labours of the shipwrights did not interfere with the loading, which went ahead steadily during the last fortnight in November.

The tanks in the hold not used for our supply of fresh water were packed with reserve stores for the ship. The remainder of the lower hold and the bunkers were filled with coal. Slowly the contents of the shed diminished as they were transferred to the ‘tween decks. Then came the overflow. Eventually, every available space in the ship was flooded with a complicated assemblage of gear, ranging from the comparatively undamageable wireless masts occupying a portion of the deck amidships, to a selection of prime Australian cheeses which filled one of the cabins, and pervaded the ward–room with an odour which remained one of its permanent associations.

Yet, heterogeneous and ill–assorted as our cargo may have appeared to the crowds of curious onlookers, Captain Davis had arranged for the stowage of everything with a nicety which did him credit. The complete effects of the four bases were thus kept separate, and available in whatever order was required. Furthermore, the removal of one unit would not break the stowage of the remainder, nor disturb the trim of the ship.

At a late date the air–tractor sledge arrived. The body was contained in one huge case which, though awkward, was comparatively light, the case weighing much more than the contents. This was securely lashed above the maindeck, resting on the fo’c’sle and two boat–skids.

As erroneous ideas have been circulated regarding the ‘aeroplane sledge’, or more correctly ‘air–tractor sledge’, a few words in explanation will not be out of place.

This machine was originally an REP monoplane, constructed by Messrs Vickers and Co, but supplied with a special detachable, sledge–runner undercarriage for use in the Antarctic, converting it into a tractor for hauling sledges. It was intended that so far as its role as a flier was concerned, it would be chiefly exercised for the purpose of drawing public attention to the Expedition in Australia, where aviation was then almost unknown. With this object in view, it arrived in Adelaide at an early date accompanied by the aviator, Lieutenant Watkins, assisted by Bickerton. There it unfortunately came to grief, and Watkins and Wild narrowly escaped death in the accident. It was then decided to make no attempt to fly in the Antarctic; the wings were left in Australia and Lieutenant Watkins returned to England. In the meantime, the machine was repaired and forwarded to Hobart.

Air–tractors are great consumers of petrol of the highest quality. This demand, in addition to the requirements of two wireless plants and a motor–launch, made it necessary to take larger quantities than we liked of this dangerous cargo. Four thousand gallons of ‘Shell’ benzine and one thousand three hundred gallons of ‘Shell’ kerosene, packed in the usual four–gallon export tins, were carried as a deck cargo, monopolising the whole of the poop–deck.

For the transport of the requirements of the Macquarie Island Base, the SS Toroa, a small steam–packet of one hundred and twenty tons, trading between Melbourne and Tasmanian ports, was chartered. It was arranged that this auxiliary should leave Hobart several days after the Aurora, so as to allow us time, before her arrival, to inspect the island, and to select a suitable spot for the location of the base. As she was well provided with passenger accommodation, it was arranged that the majority of the land party should journey by her as far as Macquarie Island.

The Governor of Tasmania, Sir Harry Barron, the Premier, Sir Elliot Lewis, and the citizens of Hobart extended to us the greatest hospitality during our stay, and, when the time came, gave us a hearty send–off.

Saturday, December 2 arrived, and final preparations were made. All the staff were united for the space of an hour at luncheon. Then began the final leave–taking. ‘God speed’ messages were received from far and wide, and intercessory services were held in the Cathedrals of Sydney and Hobart.

We were greatly honoured at this time by the reception of kind wishes from Queen Alexandra and, at an earlier date, from his Majesty the King.

Proud of such universal sympathy and interest, we felt stimulated to greater exertions.

On arrival on board, I found Mr. Martelli, who was to pilot us down the river, already on the bridge. A vast crowd blockaded the wharf to give us a parting cheer.

At 4 pm sharp, the telegraph was rung for the engines, and, with a final expression of good wishes from the Governor and Lady Barron, we glided out into the channel, where our supply of dynamite and cartridges was taken on board. Captain GS Nares, whose kindness we had previously known, had the HMS Fantome dressed in our honour, and lusty cheering reached us from across the water.

As we proceeded down the river to the Quarantine Station where the dogs were to be taken off, Hobart looked its best, with the glancing sails of pleasure craft skimming near the foreshores, and backed by the stately, sombre mass of Mount Wellington. The ‘land of strawberries and cream’, as the younger members of the Expedition had come to regard it, was for ever to live pleasantly in our memories, to be recalled a thousand times during the adventurous months which followed.

Mr E Joyce, whose name is familiar in connexion with previous Antarctic expeditions, and who had travelled out from London on business of the Expedition, was waiting in mid–stream with thirty–eight dogs, delivering them from a ketch. These were passed over the side and secured at intervals on top of the deck cargo.

The engines again began to throb, not to cease until the arrival at Macquarie Island. A few miles lower down the channel, the Premier, and a number of other friends and well–wishers who had followed in a small steamer, bade us a final adieu.

Behind lay a sparkling seascape and the Tasmanian littoral; before, the blue southern ocean heaving with an ominous swell. A glance at the barograph showed a continuous fall, and a telegram from Mr. Hunt, Head of the Commonwealth Weather Bureau, received a few hours previously, informed us of a storm–centre south of New Zealand, and the expectation of fresh southwesterly winds.

The piles of loose gear presented an indescribable scene of chaos, and, even as we rolled lazily in the increasing swell, the water commenced to run about the decks. There was no time to be lost in securing movable articles and preparing the ship for heavy weather. All hands set to work.

On the main deck the cargo was brought up flush with the top of the bulwarks, and consisted of the wireless masts, two huts, a large motor–launch, cases of dog biscuits and many other sundries. Butter to the extent of a couple of tons was accommodated chiefly on the roof of the main deck–house, where it was out of the way of the dogs. The roof of the chart–house, which formed an extension of the bridge proper, did not escape, for the railing offered facilities for lashing sledges; besides, there was room for tide–gauges, meteorological screens, and cases of fresh eggs and apples. Somebody happened to think of space unoccupied in the meteorological screens, and a few fowls were housed therein.

On the poop–deck there were the benzine, sledges, and the chief magnetic observatory. An agglomeration of instruments and private gear rendered the ward–room well nigh impossible of access, and it was some days before everything was jammed away into corners. An unoccupied five–berth cabin was filled with loose instruments, while other packages were stowed into the occupied cabins, so as to almost defeat the purpose for which they were intended.

The deck was so encumbered that only at rare intervals was it visible. However, by our united efforts everything was well secured by 8 pm

It was dusk, and the distant highlands were limned in silhouette against the twilight sky. A tiny, sparkling lamp glimmered from Signal Hill its warm farewell. From the swaying poop we flashed back, ‘Goodbye, all snug on board’.

Onward with a dogged plunge our laden ship would press. If Fram were ‘Forward’, she was to be hereafter our Aurora of ‘Hope’ — the Dawn of undiscovered lands.

Home and the past were effaced in the shroud of darkness, and thought leapt to the beckoning south — the ‘land of the midnight sun’.

During the night the wind and sea rose steadily, developing into a full gale. In order to make Macquarie Island, it was important not to allow the ship to drive too far to the east, as at all times the prevailing winds in this region are from the west. Partly on this account, and partly because of the extreme severity of the gale, the ship was hove to with head to wind, wallowing in mountainous seas. Such a storm, witnessed from a large vessel, would be an inspiring sight, but was doubly so in a small craft, especially where the natural buoyancy had been largely impaired by overloading. With an unprecedented quantity of deck cargo, amongst which were six thousand gallons of benzine, kerosene and spirit, in tins which were none too strong, we might well have been excused a lively anxiety during those days. It seemed as if no power on earth could save the loss of at least part of the deck cargo. Would it be the indispensable huts amidships, or would a sea break on the benzine aft and flood us with inflammable liquid and gas?

By dint of strenuous efforts and good seamanship, Captain Davis with his officers and crew held their own. The land parties assisted in the general work, constantly tightening up the lashings and lending ‘beef’, a sailor’s term for man–power, wherever required. For this purpose the members of the land parties were divided into watches, so that there were always a number patrolling the decks.

Most of us passed through a stage of sea–sickness, but, except in the case of two or three, it soon passed off. Seas deluged all parts of the ship. A quantity of ashes was carried down into the bilge–water pump and obstructed the steam–pump. Whilst this was being cleared, the emergency deck pumps had to be requisitioned. The latter were available for working either by hand–power or by chain–gearing from the after–winch.

The deck–plug of one of the fresh–water tanks was carried away and, before it was noticed, sea–water had entered to such an extent as to render our supply unfit for drinking. Thus we were, henceforth, on a strictly limited water ration.

The wind increased from bad to worse, and great seas continued to rise until their culmination on the morning of December 5, when one came aboard on the starboard quarter, smashed half the bridge and carried it away. Toucher was the officer on watch, and no doubt thought himself lucky in being, at the time, on the other half of the bridge.

The deck–rings holding the motor–launch drew, the launch itself was sprung and its decking stove–in.

On the morning of December 8 we found ourselves in latitude 49° 56 minutes S and longitude 152° 28’ E, with the weather so far abated that we were able to steer a course for Macquarie Island.

During the heavy weather, food had been prepared only with the greatest difficulty. The galley was deluged time and again. It was enough to dishearten any cook, repeatedly finding himself amongst kitchen debris of all kinds, including pots and pans full and empty. Nor did the difficulties end in the galley, for food which survived until its arrival on the table, though not allowed much time for further mishap, often ended in a disagreeable mass on the floor or, tossed by a lurch of more than usual suddenness, entered an adjoining cabin. From such localities the elusive pièce de résistance was often rescued.

As we approached our rendezvous, whale–birds1 appeared. During the heavy weather, Mother Carey’s chickens only were seen, but, as the wind abated, the majestic wandering albatross, the sooty albatross and the mollymawk followed in our wake.

Whales were observed spouting, but at too great a distance to be definitely recognized.

At daybreak on December 11 land began to show up, and by 6 am we were some sixteen miles off the west coast of Macquarie Island, bearing on about the centre of its length.

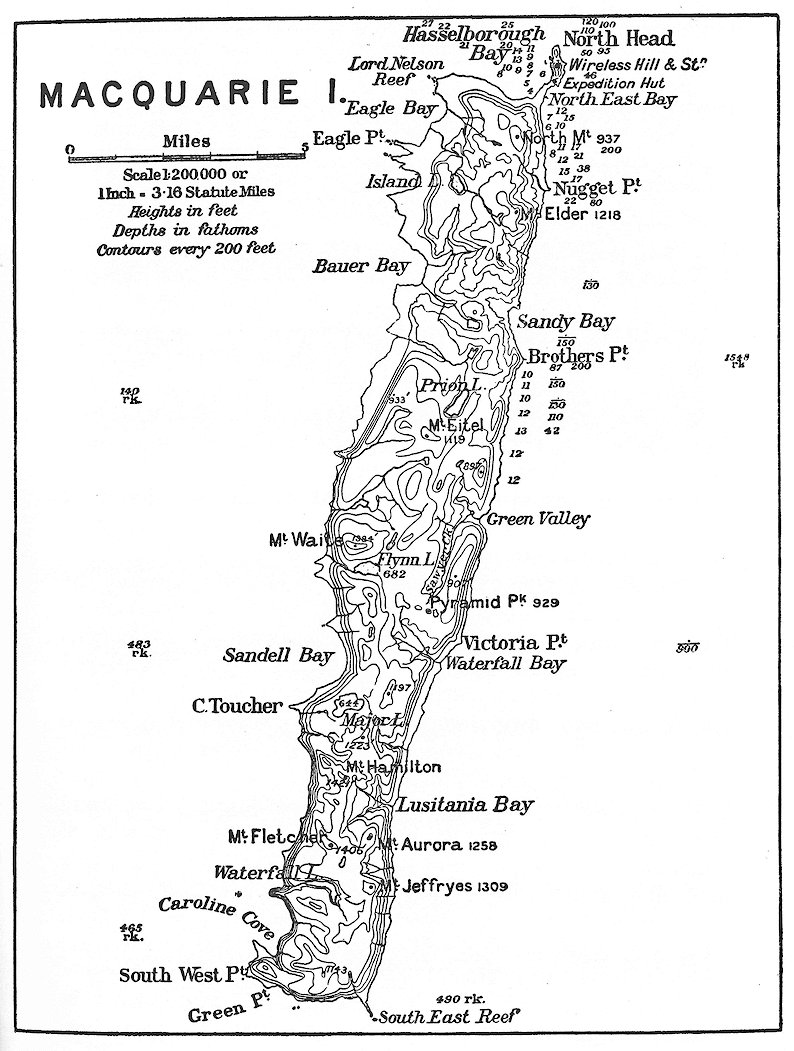

In general shape it is long and narrow, the length over all being twenty–one miles. A reef runs out for several miles at both extremities of the main island, reappearing again some miles beyond in isolated rocky islets: the Bishop and Clerk nineteen miles to the southward and the Judge and Clerk eight miles to the north.

The land everywhere rises abruptly from the sea or from an exaggerated beach to an undulating plateau–like interior, reaching a maximum elevation of one thousand four hundred and twenty–five feet. Nowhere is there a harbour in the proper sense of the word, though six or seven anchorages are recognized.

The island is situated in about 55° S latitude, and the climate is comparatively cold, but it is the prevalence of strong winds that is the least desirable feature of its weather.

Sealing, so prosperous in the early days, is now carried on in a small way only, by a New Zealander, who keeps a few men stationed at the island during part of the year for the purpose of rendering down sea elephant and penguin blubber. Their establishment was known to be at the north end of the island near the best of the anchorages.

Captain Davis had visited the island in the Nimrod, and was acquainted with the three anchorages, which are all on the east side and sheltered from the prevailing westerlies. One of the old–time sealers had reported a cove suitable for small craft at the southwestern corner, but the information was scanty, and recent mariners had avoided that side of the island. On the morning of our approach the breeze was from the southeast, and, being favourable, Captain Davis proposed a visit.

By noon, Caroline Cove, as it is called, was abreast of us. Its small dimensions, and the fact that a rocky islet for the most part blocks the entrance, at first caused some misgivings as to its identity.

A boat was lowered, and a party of us rowed in towards the entrance, sounding at intervals to ascertain whether the Aurora could make use of it, should our inspection prove it a suitable locality for the land station.

We passed through a channel not more than eighty yards wide, but with deep water almost to the rocks on either side. A beautiful inlet now opened to view. Thick tussock–grass matted the steep hillsides, and the rocky shores, between the tide–marks as well as in the depths below, sprouted with a profuse growth of brown kelp. Leaping out of the water in scores around us were penguins of several varieties, in their actions reminding us of nothing so much as shoals of fish chased by sharks. Penguins were in thousands on the uprising cliffs, and from rookeries near and far came an incessant din. At intervals along the shore sea elephants disported their ungainly masses in the sunlight. Circling above us in anxious haste, sea–birds of many varieties gave warning of our near approach to their nests. It was the invasion by man of an exquisite scene of primitive nature.

After the severe weather experienced, the relaxation made us all feel like a band of schoolboys out on a long vacation.

A small sandy beach barred the inlet, and the whaleboat was directed towards it. We were soon grating on the sand amidst an army of Royal penguins; picturesque little fellows, with a crest and eyebrows of long golden–yellow feathers. A few yards from the massed ranks of the penguins was a mottled sea–leopard, which woke up and slid into the sea as we approached.

Several hours were spent examining the neighbourhood. Webb and Kennedy took a set of magnetic observations, while others hoisted some cases of stores on to a rocky knob to form a provision depot, as it was quickly decided that the northern end of the island was likely to be more suitable for a permanent station.

The Royal penguins were almost as petulant as the Adélie penguins which we were to meet further south. They surrounded us, pecked at our legs and chattered with an audacity which defies description. It was discovered that they resented any attempt to drive them into the sea, and it was only after long persuasion that a bevy took to the water. This was a sign of a general capitulation, and some hundreds immediately followed, jostling each other in their haste, squawking, whirring their flippers, splashing and churning the water, reminding one of a crowd of miniature surf–bathers. We followed the files of birds marching inland, along the course of a tumbling stream, until at an elevation of some five hundred feet, on a flattish piece of ground, a huge rookery opened out — acres and acres of birds and eggs.

In one corner of the bay were nests of giant petrels in which sat huge downy young, about the size of a barn–door fowl, resembling the grotesque, fluffy toys which might be expected to hang on a Christmas tree.

Here and there on the beach and on the grass wandered bright–coloured Maori hens. On the south side of the bay, in a low, peaty area overgrown with tussock–grass, were scores of sea elephants, wallowing in bog–holes or sleeping at their ease.

Sea elephants, at one time found in immense numbers on all subantarctic islands, are now comparatively rare, even to the degree of extinction, in many of their old haunts. This is the result of ruthless slaughter prosecuted especially by sealers in the early days. At the present time Macquarie Island is more favoured by them than probably any other known locality. The name by which they are popularly known refers to their elephantine proportions and to the fact that, in the case of the old males, the nasal regions are enormously developed, expanding when in a state of excitement to form a short, trunk–like appendage. They have been recorded up to twenty feet in length, and such a specimen would weigh about four tons.

Arriving on the Aurora in the evening, we learnt that the ship’s company had had an adventure which might have been most serious. It appeared that after dropping us at the entrance to Caroline Cove, the ship was allowed to drift out to sea under the influence of the off–shore wind. When about one–third of a mile northwest of the entrance, a violent shock was felt, and she slid over a rock which rose up out of deep water to within about fourteen feet of high–water level; no sign of it appearing on the surface on account of the tranquil state of the sea. Much apprehension was felt for the hull, but as no serious leak started, the escape was considered a fortunate one. A few soundings had been made proving a depth of four hundred fathoms within one and a half miles of the land.

A course was now set for the northern end of the island. Dangerous–looking reefs ran out from many headlands, and cascades of water could be seen falling hundreds of feet from the highlands to the narrow coastal flats.

The anchorage most used is that known as Northeast Bay, lying on the eastern side of a low spit joining the main mass of the island, to an almost isolated outpost in the form of a flat–topped hill — Wireless Hill — some three–quarters of a mile farther north. It is practically an open roadstead, but, as the prevailing winds blow on to the other side of the island, quiet water can be nearly always expected.

However, when we arrived at Northeast Bay on the morning following our adventure; a stiff southeast breeze was blowing, and the wash on the beach put landing out of the question. Captain Davis ran in as near the coast as he could safely venture and dropped anchor, pending the moderation of the wind.

On the leeward slopes of a low ridge, pushing itself out on to the southern extremity of the spit, could be seen two small huts, but no sign of human life. This was not surprising as it was only seven o’clock. Below the huts, upon low surf–covered rocks running out from the beach, lay a small schooner partly broken up and evidently a recent victim. A mile to the southward, fragments of another wreck protruded from the sand.

We were discussing wrecks and the grisly toll which is levied by these dangerous and uncharted shores, when a human figure appeared in front of one of the huts. After surveying us for a moment, he disappeared within to reappear shortly afterwards, followed by a stream of others rushing hither and thither; just as if he had disturbed a hornets’ nest. After such an exciting demonstration we awaited the next move with some expectancy.

Planks and barrels were brought on to the beach and a flagstaff was hoisted. Then one of the party mounted on the barrel, and told us by flag signals that the ship on the beach was the Clyde, which had recently been wrecked, and that all hands were safely on shore, but requiring assistance. Besides the shipwrecked crew, there were half a dozen men who resided on the island during the summer months for the purpose of collecting blubber.

The sealers tried repeatedly to come out to us, but as often as it was launched their boat was washed up again on the beach, capsizing them into the water. At length they signalled that a landing could be made on the opposite side of the spit, so the anchor was raised and the ship steamed round the north end of the island, to what Captain Davis proposed should be named Hasselborough Bay, in recognition of the discoverer of the island. This proved an admirable anchorage, for the wind remained from the east and southeast during the greater part of our stay.

The sealers pushed their boat across the spit, and, launching it in calmer water, came out to us, meeting the Aurora some three miles off the land. The anchor was let go about one mile and a half from the head of the bay.

News was exchanged with the sealers. It appeared that there had been much speculation as to what sort of a craft we were; visits of ships, other than those sent down specially to convey their oil to New Zealand, being practically unknown. For a while they suspected the Aurora of being an alien sealer, and had prepared to defend their rights to the local fishery.

All was well now, however, and information and assistance were freely volunteered. They were greatly relieved to hear that our auxiliary vessel, the Toroa was expected immediately, and would be available for taking the ship–wrecked crew back to civilization.

Owing to the loss of the Clyde, a large shipment of oil in barrels lay piled upon the beach with every prospect of destruction, just at a time when the realization of its value would be most desirable, to make good the loss sustained by the wreck. I decided, therefore, in view of their hospitality, to make arrangements with the captain of the Toroa to take back a load of the oil, upon terms only sufficient to recoup us for the extension of the charter.

In company with Ainsworth, Hannam and others, I went ashore to select a site for the station. As strong westerly winds were to be expected during the greater part of the year, it was necessary to erect buildings in the lee of substantial break–winds. Several sites for a hut convenient to a serviceable landing–place were inspected at the north end of the beach. The hut was eventually erected in the lee of a large mass of rock, rising out of the grass–covered sandy flat at the north end of the spit.

It would have been much handier in every way, both in assembling the engines and masts and subsequently in operating the wireless station, had the wireless plant been erected on the beach adjacent to the living–hut. On the other hand, a position on top of the hill had the advantage of a free outlook and of increased electrical potential, allowing of a shorter length of mast. In addition the ground in this situation proved to be peaty and sodden, and therefore a good conductor, thus presenting an excellent ‘earth’ from the wireless standpoint. In short, the advantages of the hill–site outweighed its disadvantages. Of the latter the most obvious was the difficult transportation of the heavy masts, petrol–engine, dynamo, induction–generator and other miscellaneous gear, from the beach to the summit — a vertical height of three hundred feet.

To facilitate this latter work the sealers placed at our disposal a ‘flying fox’ which ran from sea–level to the top of Wireless Hill, and which they had erected for the carriage of blubber. On inspecting it, Wild reported that it was serviceable, but would first require to be strengthened. He immediately set about effecting this with the help of a party.

Hurley now discovered that he had accidentally left one of his cinematograph lenses on a rock where he had been working in Caroline Cove. As it was indispensable, and there was little prospect of the weather allowing of another visit by the ship, it was decided that he should go on a journey overland to recover it. One of the sealers, Hutchinson by name, who had been to Caroline Cove and knew the best route to take, kindly volunteered to accompany Hurley. The party was eventually increased by the addition of Harrisson, who was to keep a look–out for matters of biological interest. They started off at noon on December 13.

Although the greater part of the stores for the Macquarie Island party were to arrive by the Toroa there were a few tons on board the Aurora. These and the dogs were landed as quickly as possible. How glad the poor animals were to be once more on solid earth! It was out of the question to let them loose, so they were tethered at intervals along a heavy cable, anchored at both ends amongst the tussock–grass. Ninnis took up his abode in the sealers’ hut so that he might the better look after their wants, which centred chiefly on sea elephant meat, and that in large quantities. Webb joined Ninnis, as he intended to take full sets of magnetic observations at several stations in the vicinity.

Bickerton and Gillies got the motor–launch into good working order, and by means of it the rest of us conveyed ashore several tons of coal briquettes, the benzine, kerosene, instruments and the wireless masts, by noon on December 13.

Everything but the requirements of the wireless station was landed on the spit, as near the northeast corner as the surf would allow. Fortunately, reefs ran out from the shore at intervals, and calmer water could be found in their lee. All gear for the wireless station was taken to a spot about half a mile to the northwest at the foot of Wireless Hill, where the ‘flying fox’ was situated. Just at that spot there was a landing–place at the head of a charming little boat harbour, formed by numerous kelp–covered rocky reefs rising at intervals above the level of high water. These broke the swell, so that in most weathers calm water was assured at the landing–place.

This boat harbour was a fascinating spot. The western side was peopled by a rookery of blue–eyed cormorants; scattered nests of white gulls relieved the sombre appearance of the reefs on the opposite side: whilst gentoo penguins in numbers were busy hatching their eggs on the sloping ground beyond. Skua–gulls and giant petrels were perched here and there amongst the rocks, watching for an opportunity of marauding the nests of the non–predacious birds. Sea elephants raised their massive, dripping heads in shoal and channel. The dark reefs, running out into the pellucid water, supported a vast growth of a snake–like form of kelp, whose octopus–like tentacles, many yards in length, writhed yellow and brown to the swing of the surge, and gave the foreground an indescribable weirdness. I stood looking out to sea from here one evening, soon after sunset, the launch lazily rolling in the swell, and the Aurora in the offing, while the rich tints of the afterglow paled in the southwest.

I envied Wild and his party, whose occupation in connexion with the ‘flying fox’ kept them permanently camped at this spot.

The Toroa made her appearance on the afternoon of December 13, and came to anchor about half a mile inside the Aurora. Her departure had been delayed by the bad weather. Leaving Hobart late on December 7, she had anchored off Bruny Island awaiting the moderation of the sea. The journey was resumed on the morning of the 9th, and the passage made in fine weather. She proved a handy craft for work of the kind, and Captain Holliman, the master, was well used to the dangers of uncharted coastal waters.

Within a few minutes of her arrival, a five–ton motor–boat of shallow draught was launched and unloading commenced.

Those of the staff arriving by the Toroa were housed ashore with the sealers, as, when everybody was on board, the Aurora was uncomfortably congested. Fifty sheep were taken on shore to feed on the rank grass until our departure. A large part of the cargo consisted of coal for the Aurora. This was already partly bagged, and in that form was loaded into the launches and whale–boats; the former towing the latter to their destination. Thus a continuous stream of coal and stores was passing from ship to ship, and from the ships to the several landing–places on shore. As soon as the after–hold on the Toroa was cleared, barrels of sea elephant oil were brought off in rafts and loaded aft, simultaneously with the unloading forward.

We kept at the work as long as possible — about sixteen hours a day including a short interval for lunch. There were twenty–five of the land party available for general work, and with some assistance from the ship’s crew the work went forward at a rapid rate.

On the morning of the 15th, after giving final instructions to Eitel, who had come thus far and was returning as arranged, the Toroa weighed anchor and we parted with a cheer.

The transportation of the wireless equipment to the top of the hill had been going on simultaneously with the unloading of the ships. Now, however, all were able to concentrate upon it, and the work went forward very rapidly.

All the wireless instruments, and much of the other paraphernalia of the Macquarie Island party had been packed in the barrels, as it was expected that they would have to be rafted ashore through the surf. Fortunately, the weather continued to ‘hold’ from an easterly direction, and everything was able to be landed in the comparatively calm waters of Hasselborough Bay; a circumstance which the islanders assured us was quite a rare thing. The wireless masts were rafted ashore. These were of oregon pine, each composed of four sections.

Digging the pits for bedding the heavy, wooden ‘dead men’, and erecting the wireless masts, the engine–hut and the operating–hut provided plenty of work for all. Here was as busy a scene as one could witness anywhere — some with the picks and shovels, others with hammers and nails, sailors splicing ropes and fitting masts, and a stream of men hauling the loads up from the sea–shore to their destination on the summit.

Some details of the working of the ‘flying fox’ will be of interest. The distance between the lower and upper terminals was some eight hundred feet. This was spanned by two steel–wire carrying cables, secured above by ‘dead men’ sunk in the soil, and below by a turn around a huge rock which outcropped amongst the tussock–grass on the flat, some fifty yards from the head of the boat harbour. For hauling up the loads, a thin wire line, with a pulley–block at either extremity, rolling one on each of the carrying wires, passed round a snatch–block at the upper station. It was of such a length that when the loading end was at the lower station, the counterpoise end was in position to descend at the other. Thus a freight was dispatched to the top of the hill by filling a bag, acting as counterpoise, with earth, until slightly in excess of the weight of the top load; then off it would start gathering speed as it went.

Several devices were developed for arresting the pace as the freight neared the end of its journey, but accidents were always liable to occur if the counterpoise were unduly loaded. Wild was injured by one of these brake–devices, which consisted of a bar of iron lying on the ground about thirty yards in front of the terminus, and attached by a rope with a loose–running noose to the down–carrying wire. On the arrival of the counterpoise at that point on the wire, its speed would be checked owing to the drag exerted. On the occasion referred to, the rope was struck with such velocity that the iron bar was jerked into the air and struck Wild a solid blow on the thigh. Though incapacitated for a few days, he continued to supervise at the lower terminal.

The larger sections of the wireless masts gave the greatest trouble, as they were not only heavy but awkward. A special arrangement was necessary for all loads exceeding one hundredweight, as the single wire carrier–cables were not sufficiently strong. In such cases both carrier–cables were lashed together making a single support, the hauling being done by a straight pull on the top of the hill. The hauling was carried out to the accompaniment of chanties, and these helped to relieve the strain of the Work. It was a familiar sight to see a string of twenty men on the hauling–line scaring the skua–gulls with popular choruses like ‘A’ roving’ and ‘Ho, boys, pull her along’. In calm weather the parties at either terminal could communicate by shouting but were much assisted by megaphones improvised from a pair of leggings.

Considering the heavy weights handled and the speed at which the work was done, we were fortunate in suffering only one breakage, and that might have been more serious than it proved. The mishap in question occurred to the generator. In order to lighten the load, the rotor had been taken out. When almost at the summit of the hill, the ascending weight, causing the carrying–wires to sag unusually low, struck a rock, unhitched the lashing and fell, striking the steep rubble slope, to go bounding in great leaps out amongst the grass to the flat below. Marvellous to relate, it was found to have suffered no damage other than a double fracture of the end–plate casting, which could be repaired. And so it was decided to exchange the generators in the two equipments, as there would be greater facilities for engineering work at the Main Base, Adélie Land. Fortunately, the other generator was almost at the top of the ship’s hold, and therefore accessible. The three pieces into which the casting had been broken were found to be sprung, and would not fit together. However, after our arrival at Adélie Land, Hannam found, curiously enough, that the pieces fitted into place perfectly — apparently an effect of contraction due to the cold — and with the aid of a few plates and belts the generator was made as serviceable as ever.

In the meantime, Hurley, Harrisson, and the sealer, Hutchinson, had returned from their trip to Caroline Cove, after a most interesting though arduous journey. They had camped the first evening at The Nuggets, a rocky point on the east coast some four miles to the south of Northeast Bay. From The Nuggets, the trail struck inland up the steep hillsides until the summit of the island was reached; then over pebble–strewn, undulating ground with occasional small lakes, arriving at the west coast near its southern extremity. Owing to rain and fog they overshot the mark and had to spend the night close to a bay at the south end. There Hurley obtained some good photographs of sea elephants and of the penguin rookeries.

The next morning, December 15, they set off again, this time finding Caroline Cove without further difficulty. Harrisson remained on the brow of the hill overlooking the cove, and there captured some prions and their eggs. Hurley and his companion found the lost lens and returned to Harrisson securing a fine albatross on the way. This solitary bird was descried sitting on the hill side, several hundreds of feet above sea–level. Its plumage was in such good condition that they could not resist the impulse to secure it for our collection, for the moment not considering the enormous weight to be carried. They had neither firearms nor an Ancient Mariner’s cross–bow, and no stones were to be had in the vicinity — when the resourceful Hurley suddenly bethought himself of a small tin of meat in his haversack, and, with a fortunate throw, hit the bird on the head, killing the majestic creature on the spot.

Shouldering their prize, they trudged on to Lusitania Bay, camping there that night in an old dilapidated hut; a remnant of the sealing days. Close by there was known to be a large rookery of King penguins; a variety of penguin with richly tinted plumage on the head and shoulders, and next in size to the Emperor — the sovereign bird of the Antarctic Regions. The breeding season was at its height, so Harrisson secured and preserved a great number of their eggs. Hutchinson kindly volunteered to carry the albatross in addition to his original load. If they had skinned the bird, the weight would have been materially reduced, but with the meagre appliances at hand, it would undoubtedly have been spoiled as a specimen. Hurley, very ambitiously, had taken a heavy camera, in addition to a blanket and other sundries. During the rough and wet walking of the previous day, his boots had worn out and caused him to twist a tendon in the right foot, so that he was not up to his usual form, while Harrisson was hampered with a bulky cargo of eggs and specimens.

Saddled with these heavy burdens, the party found the return journey very laborious. Hurley’s leg set the pace, and so, later in the day, Harrisson decided to push on ahead in order to give us news, as they had orders to be back as soon as possible and were then overdue. When darkness came on, Harrisson was near The Nuggets, where he passed the night amongst the tussock–grass. Hurley and Hutchinson, who were five miles behind, also slept by the wayside. When dawn appeared, Harrisson moved on, reaching the north end huts at about 9 am Mertz and Whetter immediately set out and came to the relief of the other two men a few hours later.

Fatigue and the lame leg subdued Hurley for the rest of the day, but the next morning he was off to get pictures of the ‘flying fox’ in action. It was practically impossible for him to walk to the top of the hill, but not to be baffled, he sent the cinematograph machine up by the ‘flying fox’, and then followed himself. Long before reaching the top he realized how much his integrity depended on the strength of the hauling–line and the care of those on Wireless Hill.

During the latter part of our stay at the island, the wind veered to the north and north–northeast. We took advantage of this change to steam round to the east side, intending to increase our supply of fresh water at The Nuggets, where a stream comes down the hillside on to the beach. In this, however, we were disappointed, for the sea was breaking too heavily on the beach, and so we steamed back to Northeast Bay and dropped anchor. Wild went off in the launch to search for a landing–place but found the sea everywhere too formidable.

Signals were made to those on shore, instructing them to finish off the work on the wireless plant, and to kill a dozen sheep — enough for our needs for some days.

The ship was now found to be drifting, and, as the wind was blowing inshore, the anchor was raised, and with the launch in tow we steamed round to the calmer waters of Hasselborough Bay. At the north end of the island, for several miles out to sea along the line of a submerged reef, the northerly swell was found to be piling up in an ugly manner, and occasioned considerable damage to the launch. This happened as the Aurora swung around; a sea catching the launch and rushing it forward so that it struck the stern of the ship bow–on, notwithstanding the fact that several of the men exerted themselves to their utmost to prevent a collision. On arrival at the anchorage, the launch was noticeably settling down, as water had entered at several seams which had been started.

After being partly bailed out, it was left in the water with Hodgeman and Close aboard, as we wished to run ashore as soon as the weather improved. Contrary to expectation the wind increased, and it was discovered that the Aurora was drifting rapidly, although ninety fathoms of chain had been paid out. Before a steam–winch2 was installed, the anchor could be raised only by means of an antiquated man–power lever–windlass. In this type, a see–saw–like lever is worked by a gang of men at each extremity, and it takes a long time to get in any considerable length of chain. The chorus and chanty came to our aid once more, and the long hours of heaving on the fo’c’sle head were a bright if strenuous spot in our memories of Macquarie Island. In course of time, during which the ship steamed slowly ahead, the end came in sight — ‘Vast heaving! — but the anchor was missing. This put us in an awkward situation, for the stock of our other heavy anchor had already been lost. There was no other course but to steam up and down waiting for the weather to moderate. In the meantime, we had been too busy to relieve Close and Hodgeman, who had been doing duty in the launch, bailing for five hours, and were thoroughly soaked with spray. All hands now helped with the tackle, and we soon had the launch on board in its old position near the main hatch.

These operations were unusually protracted for we were short handed; the boatswain, some of the sailors and most of the land party being marooned on shore. We were now anxious to get everybody on board and to be off. The completion of their quarters was to be left to the Macquarie Island party, and it was important that we should make the most of the southern season. The wind blew so strongly, however, that there was no immediate prospect of departure.

The ship continued to steam up and down. On the morning of December 23 it was found possible to lower the whale–boat, and Wild went off with a complement of sturdy oarsmen, including Madigan, Moyes, Watson and Kennedy, and succeeded in bringing off the dogs. Several trips were made with difficulty during the day, but at last all the men, dogs and sheep were brought off.

Both Wild and I went with the whale–boat on its last trip at dusk on the evening of December 23. The only possible landing–place, with the sea then running, was at the extreme northeastern corner of the beach. No time was lost in getting the men and the remainder of the cargo into the boat, though in the darkness this was not easily managed. The final parting with our Macquarie Island party took place on the beach, their cheers echoing to ours as we breasted the surf and ‘gave way’ for the ship.