Satellite trackers tell us where the penguins travel to when they are out at sea feeding.

Penguins are fitted with transmitters before they depart to sea to feed. The trackers transmit signals that can be detected by overhead satellites. Each time a satellite receives a tracker signal, the exact location of the bird can be calculated. These locations are plotted on a map, and the positions linked together to show the entire foraging trip of the penguin whilst at sea.

We have found that the penguins feed at a range of distances from the colony on a variety of food types. The location and duration of foraging trips varies throughout the breeding season depending on the stage of the breeding cycle, sex of the bird and food availability. The extent of the sea-ice also affects the duration of foraging trips as the penguins must walk over the ice to reach open water in search of food.

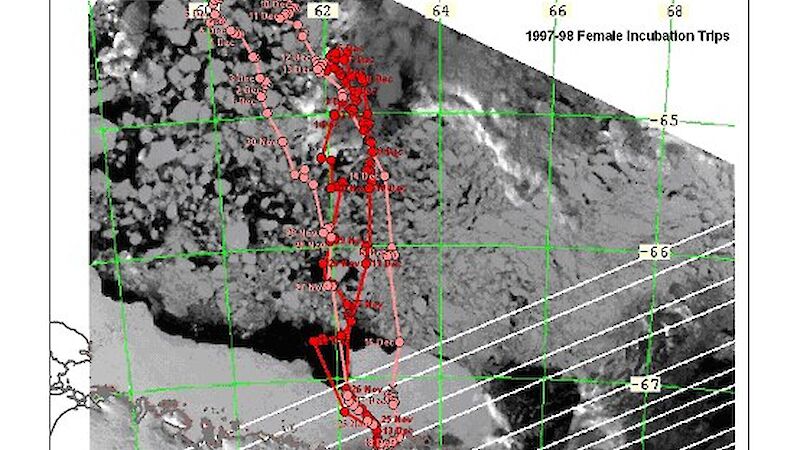

Incubation period foraging trips

During incubation of the eggs, Adélie penguins travel 200–300 km from the colony and feed on krill north of the continental shelf. These trips take 2–3 weeks to complete. The Incubation stage map above, shows the tracks of two females foraging amongst the pack ice. These birds foraged for a couple of weeks while travelling slowly northwards, and then returned home rapidly to relieve their patient partners.

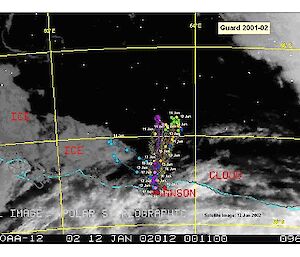

Guard-stage foraging trips

The ‘guard-stage’ is when the chicks are still small and protected in the adult’s brood patch. Penguins feeding chicks during the guard-stage undertake both local and offshore foraging trips. Local trips are within about 20 km of the colony and are carried out particularly by male Adélie penguins.

Offshore trips are carried out by birds of either sex travelling to the edge of the continental shelf, 80–120 km offshore. On return to their nest, the adults swap with their mate and take over the feeding and guarding duties. The guard-stage map above shows typical guard-stage foraging trips extending as far afield as the continental shelf edge.

If krill and fish are scarce locally the penguins must travel further away to find enough food for their chicks. In the summer of 1994–95 there was a severe shortage of krill and many young chicks starved because their parents had to travel too far away in search of food.

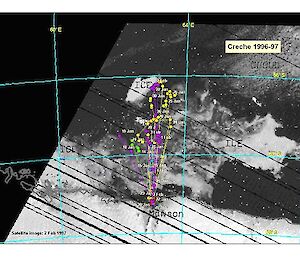

Crèche-stage foraging trips

Larger chicks need bigger meals at less frequent intervals. During the ‘crèche-stage’ (when chicks congregate into large groups, called crèches) both sexes forage mainly offshore, at the edge of the continental shelf or beyond. The adults can travel further offshore to search for food at this time as the chicks do not require the frequent feeds of the guard-stage. The tracks on the crèche-stage map above are offshore trips typical of crèche-stage foraging trips.

Pre-moult foraging trips

Once the adults have finished feeding their chicks, they conduct long foraging trips that can range far from the breeding islands. The penguins need to build up their blubber reserves at this time to prepare for a three week fast during their moult. The penguins can moult on any island or on icebergs and are not constrained to their breeding colonies. They sometimes travel hundreds of miles away from their breeding colonies at this time of year.

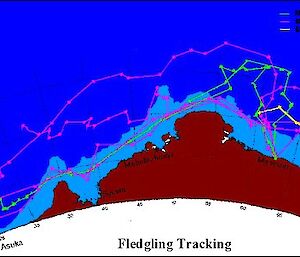

Foraging trips of fledglings and post-moult adults

Once the chicks have reached the fledging stage they leave the island and go to sea to feed for themselves. Fledging occurs in late February and coincides with the time of minimum sea-ice extent. At this time the sea ice has usually all melted, allowing the fledglings to enter the water directly from the island and start feeding straight away. The fledglings travel north of the colony and then westwards for at least four months. We do not know where they go after this, as the battery power in the satellite trackers only lasts four months. The fledglings do not return to their natal colonies until 2–5 years after hatching.

Once the adults have finished their moult, they go to sea and feed for the winter. The adults leave the colony in April for their winter feed and return the following October to breed again. During the winter they forage in amongst the pack-ice and move slowly westwards with the ocean currents for about 1,500 km. They then swing back east and return to Béchervaise Island for the following breeding season (Clarke et al. 2003).