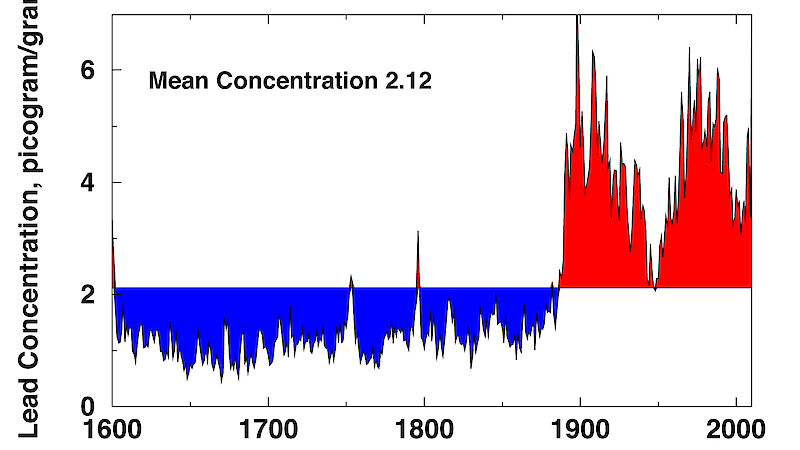

As a result, changes in atmospheric lead pollution from world events and government policies are clearly visible (see Figure 1).

“We’ve found that pollution characteristics of lead mined at Broken Hill and smelted at Port Pirie reached Antarctica by 1889,” Dr Curran said.

“This ore was exported around the world and concentrations of lead pollution in Antarctica remained high until a temporary low during the Great Depression in about 1932 and again at the end of World War II.

“The concentrations then increased rapidly until lead was eliminated from petrol in many southern hemisphere countries in the late 1990s and through the Clean Air Act in the United States.”

The discovery was made after the analysis of 16 ice cores from around Antarctica, including cores collected by Australian scientists at Law Dome.

A team at the Desert Research Institute in the United States, led by Dr Joe McConnell, used a unique ‘continuous flow analysis system’, which involved connecting an ice core melter to an instrument (a mass spectrometer) that measures lead and other chemicals continuously along the length of each core.

Precise dating of the deposition of lead pollution in the ice cores was made possible by using annual markers in the ice to count each year, and chemical signatures from volcanic events to confirm exact dates.

Dr McConnell said the research showed that some 660 tonnes of industrial lead had been deposited over Antarctica during the past 130 years, and while pollution has declined considerably, a smaller amount persists.

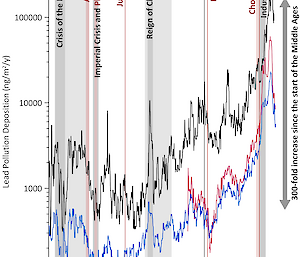

It is a similar story in the northern hemisphere, with newly published research, led by Dr McConnell, showing the correlation of lead in Arctic ice cores with the rise and fall of the Roman empire, plagues, pandemics, wars, climate disruptions and government policy (Figure 2).

“Lead pollution increased by 250 to 300 fold from the Early Middle Ages to the 1970s industrial peak, reflecting large-scale emissions changes from ancient European silver production, recent fossil fuel burning and other industrial activities,” Dr McConnell said.

“North American and European pollution abatement policies have reduced Arctic lead pollution by more than 80 per cent since the 1970s but recent levels remain about 60 fold higher than at the start of the Middle Ages.”

The rise and fall of lead observed in the Antarctic cores since the 1880s is also reflected in the Arctic results.

Despite the continued presence of lead pollution in the Arctic and Antarctic, Dr Curran said the ability to track the impacts of humans through pollution was a good news story.

“If we make science-based decisions to change our practices, and we see a positive effect, then we’ve demonstrated that it was worthwhile,” he said.