The research, published PLOS ONE in February, found krill grow annual bands in their eyestalks, much like growth rings in trees, and these correlate directly with their age.

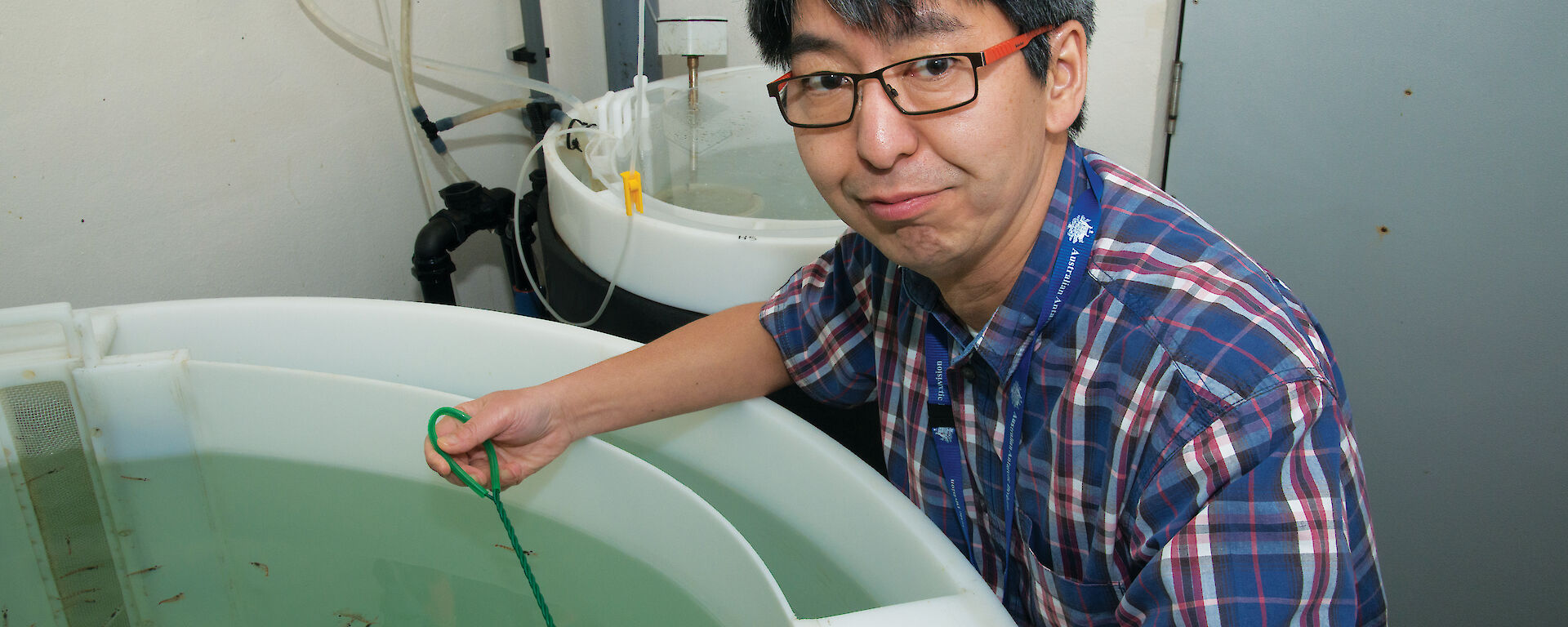

Australian Antarctic Division krill biologist, Dr So Kawaguchi, said it’s a remarkable finding.

“Despite more than 50 years of research, until now it’s been impossible to accurately assess the longevity of krill and the age structure of their populations,” he said.

“Krill don’t have any hard parts, such as ear bones, shells or scales, so we can’t determine age using these calcified structures. Additionally, there’s almost no size difference in krill beyond two years of age, and their regular moult means they can actually shrink in size, depending on the time of year and food availability.”

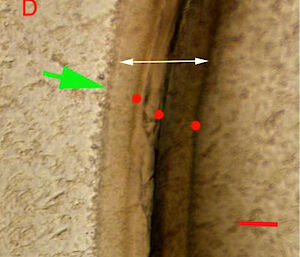

The new method, pioneered on larger crustaceans such as lobsters and crabs, involves looking at the eyestalks under a microscope.

“We look at a longitudinal section of the eyestalk to identify the light and dark growth bands and count exactly how many years the specimen has been alive.”

The ageing technique has also been successfully used on formalin-preserved samples, which means scientists can accurately determine the age of preserved krill from the early 1900s.

“The ability to retrospectively age krill allows us to compare length-at-age over time and across environments, to examine changes in the Southern Ocean ecosystem,” Dr Kawaguchi said.

The scientists studied both wild and known-age captive krill, bred in the Australian Antarctic Division krill aquarium and the Japanese Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium.

The age-based assessment methods will provide information on stock structure to assist with catch limits and management options for the krill fishery through the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources.

“Krill are a keystone species in the Southern Ocean, predated by penguins, seals, flying seabirds and whales, so any fishery needs to be carefully managed,” Dr Kawaguchi said.

“The Southern Ocean is also undergoing major changes in the sea-ice zone, in primary production and through ocean acidification, so a better understanding of how long they live will help us more accurately predict the potential impacts of climate change on krill.”

The research is a joint project* of the Australian Antarctic Division, the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (USA), University of New Brunswick (Canada), Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium and the National Research Institute of Far Seas Fisheries (Japan). It was partly funded through a grant from the Antarctic Wildlife Research Fund (Australian Antarctic Magazine 29: 5, 2015).

Nisha Harris

Australian Antarctic Division

*Australian Antarctic Science Project 4037