Adélie penguin populations in East Antarctica have almost doubled over the past 30 years according to new research published in PLOS ONE in October.

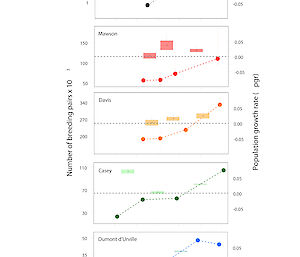

Australian Antarctic Division seabird ecologists, Dr Colin Southwell and Dr Louise Emmerson, alongside colleagues from France and Japan, found that the five main regional populations of Adélie penguins in East Antarctica had increased between 1.8% and 2.5% per year since 1980.

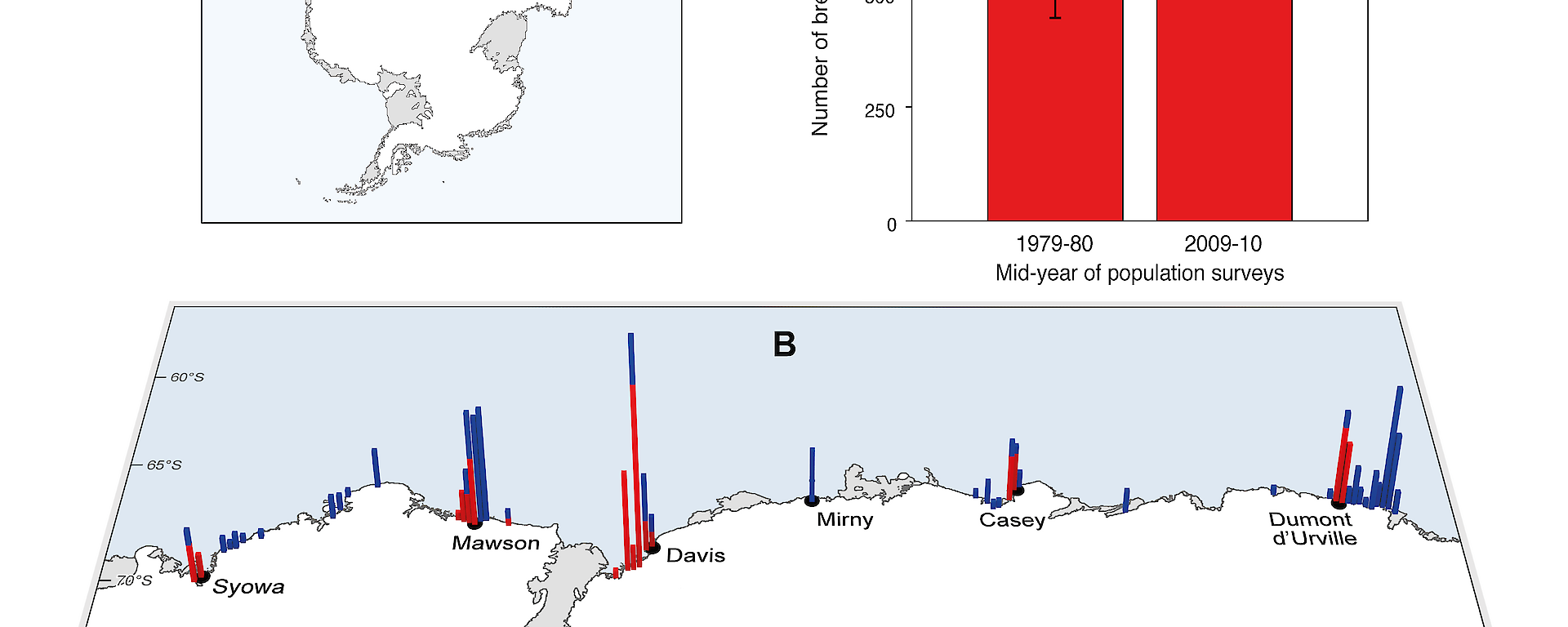

Using aerial photographs and ground-based observations, the team counted Adélie penguins during recent summer breeding seasons at 99 breeding sites located along 4500km of the East Antarctic coastline.

The breeding sites were distributed amongst five regional populations – close to the French station Dumont d’Urville, Australia’s Casey, Davis and Mawson stations, and Japan’s Syowa station. They included over 70% of the known breeding sites in East Antarctica.

The team compared these recent population counts with historical counts made at the same sites 30 years ago. From this they estimated rates of population change across the entire East Antarctic area, and at regional and local scales.

‘We found that the overall population across sites had increased by 69% at an average rate of 1.9% per year,’ Dr Southwell said.

The researchers then examined the relationship between population changes and environmental conditions over shorter time scales at 72 of the sites.

‘We saw a faster rate of population increase five years after periods when winter sea ice cover decreased,’ Dr Emmerson said.

‘This probably indicates that changes in winter sea-ice primarily affect young penguins before they become breeders at around five years old.’

Although population surveys have been made at many breeding sites, scientists have only snapshots of penguin numbers in time. This makes it difficult to identify exactly how changing environmental conditions affect population growth. However a number of hypotheses have been advanced.

‘Two aspects of the East Antarctic marine environment have changed over a large area and at a time that may be linked to the long-term population increase,’ Dr Southwell said.

‘Firstly, the harvesting of baleen whales, krill and fish across East Antarctic waters through the 20th century could have altered the food web dynamics and reduced competition with other species for food.

‘Secondly, a proposed reduction in sea-ice extent around Antarctica in the mid-20 century may have benefited Adélie penguins by enabling better access to the ocean for foraging.’

Despite the consistent increase in the five regional populations, local population growth rates within the regional populations varied between 11.4% to −5.8% per year. This variation indicates that local processes – such as localised prey depletion or limited breeding habitat – affect population growth in addition to regional processes such as reduced competition and sea-ice change.

The population increase in East Antarctica contrasts strongly with widespread decreases in the West Antarctic Peninsula over the same time.

‘With Adélie penguins there is a delicate balance between too much and too little sea ice for accessing foraging grounds, capturing prey and resting,’ Dr Emmerson said.

‘It has been proposed that in areas where ice is very extensive, such as East Antarctica, a reduction in sea-ice extent will initially benefit the species up to a point, and then further reductions will be detrimental – as we are seeing in West Antarctica.’

The study authors said the future global status of Adélie penguins will depend on the complex interplay between the changing physical environment and the effects of human activities such as fishing and tourism.

‘Further studies such as this that look at penguin responses over space and time and in different environments are critical for understanding ecosystem change and improving predictions of future changes in Adélie penguin populations,’ Dr Emmerson said.