Satellite imagery and aerial surveys have revealed a previously unseen breeding behaviour amongst emperor penguins in Antarctica, with four colonies found to be rearing their chicks on ice shelves.

Emperor penguins were thought to breed mainly on sea ice attached to the continent (known as ‘fast ice’), putting them at risk from climate-related changes to sea ice thickness, extent and duration.

However, scientists from the British Antarctic Survey, Australian Antarctic Division and the University of California, confirmed their breeding activity on ice shelves in the journal PLOS ONE in January this year.

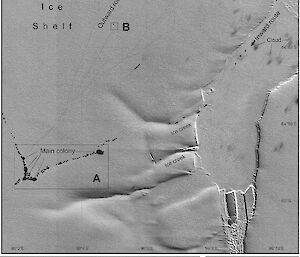

The four colonies were discovered on the West Ice Shelf and Shackleton Ice Shelf in East Antarctica, the Nickerson Ice Shelf in West Antarctica and the Larsen C Ice Shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula.

‘Emperor penguins have previously been considered sea ice obligate species, with 44 of the 46 colonies located on sea ice, and the other two small colonies located on land,’ the study authors wrote.

‘Of the colonies found on ice shelves, two are newly discovered, and these have been recorded on shelves every season that they have been observed. The other two have been recorded both on ice shelves and sea ice in different breeding seasons.’

Australian Antarctic Division penguin ecologist and co-author of the paper, Dr Barbara Wienecke, said it was not clear whether the breeding behaviour was a new phenomenon associated with recent climate change or one that had always existed but was not previously documented. Regardless, the discovery has implications for population modelling of the species, as it could mitigate some of the consequences of sea ice loss.

‘Breeding on ice shelves may be an adaptation employed by emperor penguins when sea ice conditions are poor, but this is only possible where emperor penguins have access to the top of an ice shelf. This is not the case at all colony sites,’ Dr Wienecke said.

‘Of the four colonies we observed, three were located in areas with marginal sea ice conditions.

‘Potential benefits, and whether these are permanent or temporary, need to be considered and understood before further attempts are made to predict the population trajectory of this species.’

Recent estimates suggest the emperor penguin population (about 238 000 breeding pairs) will halve by 2052 as sea ice declines, with the complete loss of more northerly colonies above 70° South. This led the IUCN to re-list the species from ‘Least Threatened’ to ‘Near Concern’.

Dr Wienecke cautioned that even if the study reflects an adaptive response to a warming environment, the penguins will still face changes in the Antarctic food web and increased predation and competition, which will affect breeding success and survival rates. Ice shelves also pose a number of risks, including a lack of shelter, exposure to katabatic winds and possible calving of the ice front.

The discovery opens up other questions such as how do emperor penguins access the ice shelves, does the breeding cycle differ on ice shelves compared to fast ice, and what is the energetic cost of reaching the top of an ice shelf? It also invites questions of other species.

‘This previously unknown and surprising behaviour recorded in such an iconic animal suggests that other species may also be capable of unpredicted or unknown behavioural adaptations in a future warming world,’ the study authors conclude.

Fretwell PT, Trathan PN, Wienecke B, Kooyman GL (2014). Emperor Penguins Breeding on Iceshelves. PLOS ONE 9 (1). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085285

Wendy Pyper

Corporate Communications, Australian Antarctic Division