Amateur radio operator Craig Hayhow has used the moon to bounce a radio signal 742 000km, from Mawson station in Antarctica to Cornwall in England.

Proving the feat was no accident, two nights later he performed another ‘moon bounce’ to communicate with radio operators in Sweden and New Zealand.

‘The “Holy Grail” for many serious amateur radio operators is bouncing a radio signal off the moon and reflecting it back to Earth to have a conversation with another station on the other side of the world,’ Craig says.

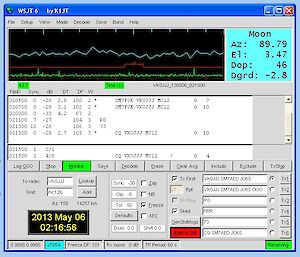

‘The technical challenges are immense, but with modern high speed computers and sophisticated software, it has become a lot easier in recent years.’

Craig, who is wintering at Mawson station as a Senior Communications Technical Officer, says his first moon bounce on May 4 this year, was the first time it had been achieved from an Australian Antarctic station and only the third time from the Antarctic continent.

Until recently, the technique was only possible using the largest, most powerful and expensive amateur radio stations. This is because of the distance the signal has to travel, the amount of power needed to send a strong signal and the loss of signal as it travels through space.

‘The moon has to be lined up perfectly between the two stations to achieve an adequate reflection, so we use computer programs to find the optimum time to communicate,’ Craig explains.

‘However, most of the transmitted signal is lost into free space and only about seven per cent of the signal that strikes the moon is reflected; the rest is absorbed.

‘The Earth’s atmosphere distorts and attenuates the signal even further so that by the time the signal reaches the receiving station it is very weak.’

As Craig is operating from a small, ‘home-made’ station, he can only communicate with receiving stations that use multiple, ‘high gain’ antennas and vast amounts of power.

Craig built his own radio station using an off-the-shelf antenna that is small enough not to get blown away in a blizzard, but large enough to generate a signal that can reach the moon. He also built an amplifier to boost his transmitting signal from 4 watts to 500 watts.

To bounce a signal off the moon he uses customised software to target it. Objects other than the moon can also be used and Craig has targeted commercial aircraft and meteor trails.

‘The software is tailored for each application,’ he says.

‘It takes around 2.7 seconds for a signal to be bounced off the moon, while it is virtually instantaneous from an aircraft. If a signal comes back, you can be sure it’s reflected off the object you are targeting.’

Craig passed the exams to become an amateur radio operator when he was 17 and some 30 years later he still enjoys the surprise of chatting to people from around the world, sometimes in remote or unusual places. As Antarctica is also considered ‘remote’ and ‘unusual’, Craig says he is often bombarded by operators clamouring to add his unique call sign to their log books.

Craig’s moon bounce achievement comes 100 years after the first radio communication between Antarctica and Australia, via Macquarie Island, was established by the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE, 1911–1914), led by Douglas Mawson. The AAE was the first Antarctic expedition to use radio communications, using ground waves (Very Low Frequency or VLF). Sadly, Mawson’s first use of the radio, on 24 February 1913, was to relay news of the deaths of his companions, Xavier Mertz and Belgrave Ninnis, during the Far Eastern sledging journey.

Fortunately, Craig’s experiences are happier.

‘Usually the talk is of a technical nature, but we also talk about work, family and the places we live,’ he says.

‘However, amateur radio is mostly about furthering the science of radio by testing, research and development, and sharing ideas within the radio community.’

Wendy Pyper

Australian Antarctic Division