Australia claimed some 42 per cent of the Antarctic continent1 by the mid 1900s, but this ambitious claim was tenuous to say the least. It was based largely on the exploration voyages of Douglas Mawson in 1911–14 (the Australasian Antarctic Expedition) and his BANZARE voyages of 1929–30 and 1930–31.

A great deal of Antarctic coastline had been examined. Some land-based coastal exploration had been achieved during the AAE, and the BANZARE voyages had covered much territory to the west of the future Australian claim, although they had made only four brief landings due to the inability of Mawson’s wooden ship Discovery to penetrate the pack ice. Claiming territory depended on certain formalities, including building a rock cairn, raising a flag and reading a proclamation. On the first BANZARE voyage this was only achieved on Proclamation Island off the coast of Enderby Land in January 1930.

Other efforts to claim land bordered on farce. There were the flag and proclamation cylinder lobbed up on to rocks from a ship’s boat near the Murray Monolith (which unfortunately rolled back into the water), and Sir Douglas’ use of the expedition’s Gypsy Moth float plane to fly inland and heave over a Union Jack onto the featureless ice below, while reading the proclamation aloud from the front seat of the little biplane, piloted by Stuart Campbell. On the second BANZARE voyage Mawson and four of his men landed briefly at Scullin Monolith, where they erected a flag and repeated taking possession on 13 February 1931.

One of the key conditions of territorial claims involved what was defined as ‘a sufficient display of authority’ in the area in question. This included exploration, science, fishing, whaling — in other words actually being there and doing something. By 1946, Australia was doing precious little of that. Sir Douglas Mawson, however, was on the case and was urging the Australian Government to consolidate Australia’s Antarctic claims. With concern about Norwegian exploration in Antarctica during the 1930s, and USA interest in the 1940s, an interdepartmental Executive Committee on Exploration and Exploitation held its first meeting in January 1947 (with Sir Douglas Mawson acting as an adviser) to plan what might be done.

On 9 July 1947 ANARE (Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition) – the ’s’ was added later – was formed to create research stations on Heard and Macquarie islands, and to send a ship to the Antarctic continent to try and find a suitable site for an Australian station. Group Captain Stuart Campbell was appointed the Leader of ANARE and a young physics lecturer at the University of Melbourne, Phillip Law, was appointed Senior Scientific Officer.A flurry of action saw three voyages scheduled for later that year. Two subantarctic stations were planned; one on Heard Island and the other on Macquarie Island. The only ship that could be found for this task was a former World War II LST (Landing Ship Tanks). The vessel could be run up on a hostile shore, a landing platform lowered from its blunt bows, and tanks, troops and other equipment quickly got ashore. How it would fare in the Southern Ocean no one really knew. While HMAS LST 3501 voyaged first to Heard Island and then to Macquarie Island, an attempt would be made to send another ship, the improbably named HMAS (no less) Wyatt Earp south to the Antarctic continent to carry out scientific work and try and find a suitable location for an Australian station.

Wyatt Earp, a converted Norwegian herring trawler of only 270 tons, had been used by the American explorer Lincoln Ellsworth to support his attempts to be the first to fly across the Antarctic continent — achieved in 1939. He named the ship after his boyhood hero, the gun-slinging Marshall of Dodge City. After his continental flight he gave the ship to his deputy leader, Sir Hubert Wilkins, who in turn sold it to the Australian Government (with Sir Douglas Mawson’s support). It was the last time an official Australian Antarctic expedition would go south in a wooden ship with sails — although it did have a diesel engine. ANARE’s new Chief Scientific Officer Phillip Law voyaged on Wyatt Earp to conduct experiments into cosmic rays in southern latitudes. It rolled abominably, and Law later wrote that Captain Cook’s ship Resolution ‘was twice as big and I venture to say twice as comfortable’.

HMAS Wyatt Earp was totally unsuitable for its mission and as Phillip Law said, ‘as an icebreaker this ship was a gnat’. After two false starts the ship finally sailed on 7 February 1948, far too late in the season to do any useful work and unable to penetrate the pack ice to reach the continent.Clearly the establishment of a continental station would have to wait for a suitable ship, and that could be many years away. Group Captain Stuart Campbell was a born adventurer and could not bear the thought of the routine boredom of running the Heard and Macquarie island stations indefinitely, and resigned. Phillip Law succeeded him in 1949 and headed the Antarctic Division for the next 17 years, coordinating ANARE’s scientific programs and personally leading the exploration of 5000km of uncharted Antarctic coastline.

But it was not until 1953 that a suitable steel, ice-strengthened ship, the Danish-built Kista Dan, could be found, which could breach the Antarctic pack ice and establish Australia’s first mainland Antarctic station. But where would this be? Law knew that it was essential to build a station on solid rock, rather than on the moving Antarctic ice sheet, which would inevitably break off the coast as an iceberg, taking the station with it. Options were narrowed considerably when Law gained access to aerial photographs of the Antarctic coastline, taken by the United States Navy during Operation High Jump, in the summer of 1946–47.

Law was particularly interested in a part of the Mac.Robertson Land coast, between longitudes 60°E and 70°E, to the west of Australia’s Antarctic claim. Here, the aerial photographs revealed outlying rocky islands, a small area of exposed rock on the mainland nearby, and interesting looking mountains close to the coast. Best of all, Law, peering at the black and white photographs through a magnifying glass, thought he could determine the rocky arms of what might be a natural harbour.

In 1953 the Antarctic Division’s charter of the Kista Dan brought the establishment of Australia’s first Antarctic station a step closer. But first, the Macquarie and Heard island stations would have to be resupplied. The logistics were formidable, as Kista Dan would have to carry supplies for Heard Island and building materials and all supplies (including a team of husky dogs) for the new Antarctic station. Law convinced the Executive Planning Committee that the best site for the station was most likely Mac.Robertson Land. Because of the long return journey from Melbourne via Heard Island to the Mac.Robertson Land coast — some 8000 nautical miles — it was necessary to take on resupplies of fuel and fresh water somewhere along the route. Fortunately the French government agreed to provide both from their scientific station at the Isles de Kerguelen, about 300 nautical miles north-east of Heard Island.

On 4 January 1954 the Minister for External Affairs, Richard Casey, farewelled Kista Dan from Melbourne, on what would be a voyage of high adventure, near disaster, and ultimate success. After leaving Kerguelen on 24 January, heading for the coast of Mac.Robertson Land, Kista Dan entered loose pack ice on 1 February and made relatively good progress. The following day Captain Petersen called Law to the bridge saying he could see rocky islands ahead. Law climbed to the crows nest and was exhilarated to see not rocky islands, but the peaks of the Framnes Mountains, recognisable from the aerial photographs he had studied so closely in Melbourne. When Kista Dan entered a small polynya of open water, Law arranged for floats to be fitted to one of the two Auster aircraft carried on board, and took off with pilot Doug Leckie for an aerial reconnaissance. Law later wrote: ‘From 3000 feet altitude the view was superb, but disheartening. My elation of the morning vanished. Ahead were several miles of pack ice and beyond it some open water. But this open water, that I thought would extend to the coast, continued for another 3 miles before it was replaced by fast ice – a blue-grey expanse of solid, unbroken ice, smooth and polished, with no snow cover – that stretched on for some 16 miles to the shore. However Law was delighted to see that the ship had been spot on track to reach the site viewed from the Operation High Jump photos. Not only that, the harbour (later called Horseshoe Harbour) and its rocky shoreline looked, from the air, an ideal location for the new station.In later years Law realised they were unlucky to strike so much fast ice so late in the season, which usually breaks out in late January. But bigger problems were soon encountered. Captain Petersen told Law that he thought it would take him at least a week to break Kista Dan through the fast ice to the coast. With the summer season fast slipping away, Law was concerned that they would not have enough time to put up the pre-fabricated huts and unload all the equipment in the time left. He decided to unload some of the stores on the fast ice and use three Weasels (over-snow tractors) to get to Horseshoe Harbour and begin work, while the ship broke her way through. On 5 February Law and Leckie took off in one of the Austers (its floats now replaced with skis) to land near Horseshoe Harbour for a closer inspection of the station site. Law: ‘We landed on the blue, pebbly, highly polished ice and our skis clattered and bumped as we ran on towards an iceberg about a third of a mile ahead. The friction of the skis on the glassy ice was so low that we showed little sign of slowing down and the wall of ice ahead began to loom frighteningly close. Just as I was envisaging all sorts of dramatic results of an impending impact with the iceberg, Leckie took the desperate measure of putting the plane into a ground loop. As we spun around and around, still clattering onwards, the extra friction of the edges of the skis pushing sideways across the surface had the desired effect and we came to rest a bare 30 yards from the 60-foot wall of the berg face.’

Law was able to walk across the fast ice, still filling Horseshoe Harbour, to the planned site for Mawson station, sketching and taking photographs. Meanwhile Bob Dovers and two Weasels were on their way across the ice towards the coast. Kista Dan was making slow progress through the ice, and the normally equable Captain Petersen was objecting when asked to re-load some of the cargo put down on the ice. Later that day Dovers radioed to say that one of his Weasels had broken through the ice and that rescue efforts had failed, and that he planned to move on to a rocky island for the night. The following day the wind picked up to gale force, and on 7 February – to complicate matters – the fast ice started its annual breakup, with huge slabs of floating ice building up around Kista Dan and threatening to crush the ship. The Captain got so worried about the safety of the ship at one point that he ordered all ANARE personnel on deck. But disaster was averted. Law: ‘We had survived one of the major hazards to an Antarctic ship. Thank God for a welded steel ship with close frames and thick plates!’Kista Dan had to be dug out of its icy embrace with crowbars and explosives. The breakout of the fast ice enabled the ship to make better progress so that by 11 February Kista Dan had pushed her way through the encircling rocky arms of Horseshoe Harbour. Unfortunately the ship spent the night broadside to the wind, and in the morning Law was appalled to find that the two Auster aircraft on board had been wrecked by high winds — a bitter blow to the further exploration of the coast.

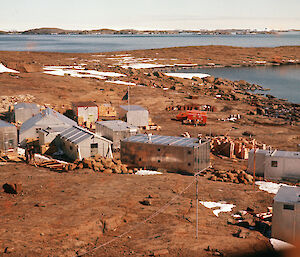

Unloading could now take place over the sea ice, with Weasels pulling sledges on to the station site, including specially designed barge caravans that could shelter workers before the prefabricated huts could be erected. On 13 February Law raised the Australian flag between two red barge caravans and officially named ANARE’s first continental station Mawson, ‘in honour of the great Australian explorer and scientist Sir Douglas Mawson’.

Meanwhile the RAAF fitters had worked miracles and patched together a flyable Auster out of the remains of Austers 200 and 201. There were no flaps and no tail fin, but fly it did. Captain Petersen jokingly named it Auster 200.5.

By Wednesday 17 February unloading was completed and all hands then helped with erecting the huts in which the 10 pioneering expeditioners would live for the next year. By 23 February Captain Petersen was concerned that Kista Dan might be frozen in, and the ship had to be broken out by everybody wielding crowbars and picks. Finally the ship broke free, sounded her siren, and as the 1954 wintering party waved farewell from the shore, Kista Dan slowly began to break her way out towards open water.Against all the odds, Australia finally had its first station on continental Antarctica.

TIM BOWDEN

Tim Bowden is the author of the ANARE Jubilee History, The Silence Calling — Australians in Antarctica, 1947–97 published by Allen & Unwin.

- Following a British Order in Council in 1933, the subsequent passing of the Antarctic Territory Acceptance Act by the Australian Parliament that same year, and proclaimed in 1936.