Four Sydney residents of Mawson’s 1911–1914 Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) gathered in the Presbyterian section of Gore Hill Cemetery on a dismal day in May 1922. Dr Sydney Jones, Dr John Hunter, Charles Laseron and Walter Hannam were farewelling Dr Archie McLean, a man they deeply admired. Their reunion under different circumstances would have been a cheerful affair. Mawson’s expeditioners were united by the Australian sense of humour, their understanding of Antarctic perils, their explorer’s curiosity, and the desire to unlock the scientific secrets of Macquarie Island and the Antarctic continent. The death of the expedition’s Chief Medical Officer was a time to remember his commendable achievements and to consider their own Antarctic contributions and what their futures would be.

Dr Archibald Lang McLean

Upon his return from Antarctica, Five Dock Public School presented McLean with a pen, demonstrating pride in their past student’s achievements. Graduating from Sydney University in Arts and Medicine, McLean worked briefly as Resident Medical Officer at Lewisham and Coast Hospitals, before joining Mawson’s AAE with fellow medical graduate, Dr. Sydney Evan Jones. McLean was assigned to Mawson’s Main Base, and Jones to Frank Wild’s Western Party. Although separated by over 1,600 km of hazardous coastline, they worked together en route, providing veterinary care of the sledge huskies and performing autopsies on those that died on the voyage.

McLean’s non-medical duties included cooking and mess duties, lighting the range, and contributing to the construction of the Main Hut. He took meteorological and tidal observations and assisted with the erection of the wireless masts. McLean was the first to record electrical effects – he noticed St. Elmo’s fire, a discharge of electricity on the points of the nephoscope.

Bacteriology and physiology were McLean’s research focus. He studied changes in the blood and general health of his comrades by taking monthly blood smears and swabs from the ears, nose and throat. He determined that it took about six weeks for expeditioners to acclimatise and that during periods of constant exercise the red blood cell count rose dramatically. Interested in the physical and psychological wellbeing of the expeditioners, McLean was affectionately called ‘Dad’.

McLean made significant contributions to sledging journeys. Initially venturing south with Eric Webb and Frank Stillwell, he then made the arduous 400 km eastern journey with Cecil Madigan and Percy Correll. They traversed sea ice and a dangerous glacier tongue to map the coastline east of Main Base and climb Aurora Peak. They named Penguin Point after the Adélie penguin that startled them on their arrival. Madigan and Correll completed a geological survey, while McLean collected lichens, algae and mosses, and studied a variety of birds.

When Mawson’s sledging party was overdue, McLean selflessly remained at Main Base with 5 others to find their missing members, while most Antarctic expeditioners departed on the Aurora as planned. McLean performed varied tasks in this unplanned second year. He treated Mawson’s injuries and transformed him from near death to a full recovery over the ensuing 2 months. He cared for Jeffryes, who suffered from periods of paranoia and delusions. He kept the biological log and helped Mawson to sort biological specimens for inclusion in John Hunter’s collection. He also edited the seven editions of The Adélie Blizzard – a witty publication of expeditioners’ verse, articles, letters, and short stories, designed to lift morale during the winter.

After the AAE McLean attended Mawson’s wedding and sailed to England with Mawson and his new bride, Francisca Adriana (Paquita). McLean assisted Mawson in writing The Home of the Blizzard and the AAE’s scientific work, and his literary contribution was well regarded. John King Davis, Master of the Aurora, also relied on McLean’s literary expertise while penning his book, With the “Aurora” in the Antarctic, 1911–1914. While in England McLean met his wife, Eva Maud Yates. He also served in the Royal Army Medical Corps, but was discharged with appendicitis.

While recovering his health in Australia, McLean worked at the Gladesville Hospital for the Insane, and continued with his Medical Doctoral thesis Bacteriological and other researches in Antarctica, which gained him the University Medal and the Ethel Talbot Memorial Prize. This outstanding work included bacteriological investigations, physiology, immunity, dietetics and psychology in Antarctic conditions.

McLean’s altruistic conduct in Antarctica continued when he rejoined the war effort, as a Captain with the Australian Imperial Forces. Having established a medical post at Péronne on 31 August 1918, McLean treated 200 men in 18 hours of constant work under intense artillery fire, earning the Military Cross to add to his British War Medal and Victory Medal. During his recovery from being gassed he assisted in collating a medical history of the war. He was discharged on medical grounds, having contracted pulmonary tuberculosis while performing medical duties. He became the Medical Officer for the Red Cross War Chest Farm Colony at Beelbangera, but his tuberculosis worsened and he died aged 37.

His loss was widely felt, being reported by newspapers across Australia and in The British Medical Journal and The Medical Journal of Australia. His outstanding contribution to polar medical research set the standard of exceptional quality that today’s doctors follow. He provided expert treatment to patients during his work in Australian hospitals, to Antarctic expeditioners, and to service personnel during the War, saving thousands of lives – including Mawson’s.

McLean’s funeral was attended by his Antarctic comrades, Hunter, Laseron, Hannam and Jones, who all lived long lives and made significant individual contributions. The men agreed with Reverend Maynard Riley’s description of McLean: ‘He gave his life to his fellow men. As a student he was zealous and accurate, and in Antarctica he revealed some fine traits … When his research work was taken and considered, many in the future would thank God that he lived.’

Dr Sydney Evan Jones

Although Adelaide born, Jones grew up in Queensland, where his academic excellence was recognised with the Lilley Medal for the highest results in the state. Graduating in medicine from Sydney University, Jones completed a year as resident medical officer with the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, before becoming the doctor for Mawson’s eight-man Western Party. Like McLean, Jones’s duties were not confined to medicine; he helped construct the hut named ‘The Grottoes’, and an igloo for the magnetic observatory. He contributed to The Glacier Tongue, the station’s publication of poetry and articles. He was plumber, brazier, tinsmith and cook, and worked the acetylene plant. Thoughts of marrying Olive Booth, whose image hung beside his bed, sustained Jones during the most difficult times.

Jones made crucial contributions to the success of sledging journeys. His inventiveness and persistence were illustrated by his experiments with Glaxo, a powder made from milk and cream, which produced a high energy biscuit. This enabled more life-sustaining food to be carried on sledging journeys. In August 1912 Jones and 5 comrades set out in −37°C to lay a depot of provisions for the summer sledge journey. During this trek, 5 anxious and uncomfortable days were spent sheltering from the elements – they could hear the avalanches over the 160 km/h wind gusts.

In November, Jones, George Dovers and Charles Hoadley sledged past the Helen Glacier and discovered a group of rocky islets. They named Haswell Island, which was rich in bird life – an emperor penguin rookery, Adélie penguins, silver-grey petrels, Wilson and Antarctic petrels, Cape pigeons, and skua gulls stealing unattended eggs. Jones described the sound from the penguin rookery as similar to sports spectators at an exciting game. They reached Gaussberg, then returned to The Grottoes, having made scientific advances and charted 643 km of coastline. Jones Rocks and Jones Ridge are Antarctic landmarks named in his honour.

After his Antarctic experience, Jones was a doctor at Parramatta, Rydalmere and Callan Park psychiatric facilities in Sydney. Jones’s interest in psychiatry may have been inspired by McLean’s challenges in caring for Jeffryes during his year at Main Base, or his own psychological adjustment to life without his wife, Olive, who died from post natal complications in 1916. Jones provided psychiatric care for many returned Australian soldiers who were traumatised from their experiences of war. By the end of 1918, 941 service personnel had been successfully treated and reintegrated into the Australian community.

Jones is described as a pioneer of psychiatric treatments, using a holistic approach that included psychoanalytical therapies and the use of plants and animals in patient care. Jones became the Medical Superintendent of Broughton Hall in 1925, until his death in 1948, and is credited with creating a hospital of teaching excellence. Jones’s early intervention approach was followed by other psychiatric clinics in the 1930s. Broughton Hall’s Evan Jones Lecture Theatre was named in his honour. Jones also led the neurology and psychiatry section of the British Medical Association (New South Wales Branch) and helped establish the Australasian Association of Psychiatrists, illustrating his commitment to improving psychiatric practice.

Dr John George Hunter

Attending the same high school and University as McLean, Hunter was the Main Base Party’s biologist. His valuable contribution to the expedition was recognised in the naming of Mount Hunt and Cape Hunter. Hunter’s collection of samples included mosses, lichens, insects, red and brown star-fish, marine worms, jellyfish, pteropods and small fish.

Hunter’s utmost respect for McLean’s personal and professional attributes may have influenced his decision to return to Sydney University and become a medical practitioner. On graduation in 1916, Hunter worked in surgery and medicine as a resident at the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children. He married nurse Clarice Mary Walker, before joining the Australian Army Medical Corps. Like McLean, he served in England and France and was the recipient of medals for his outstanding service, including: British War, Victory, War, Australian Service, King’s Jubilee and Coronation medals. During World War 2 he was a Major in the home militia, responsible for staff and medical duties.

Hunter’s civilian positions included that of general practitioner at Mascot and Botany, assistant physician at Sydney Hospital, honorary physician at Royal South Sydney Hospital, and lecturer of medical ethics at Sydney University. From 1929 he was secretary of the New South Wales branch of the British Medical Association (BMA), organising the BMA’s first post graduate course for medical practitioners. He served as Australasian secretary of the World Medical Association and chaired the Australian Council of Social Service (1961–64). He was crucial to the formation of the Australian Medical Association (AMA), drafting its code of ethics. He was awarded the BMA (Australia) gold medal and in 1957 was appointed CBE. As a demonstration of the high regard felt for this committed doctor, the AMA created the JG Hunter fund, providing scholarships in his honour, and his portrait hangs in the AMA’s Canberra office. He died in 1964, sadly missed by Clarice and their 5 children.

Charles Francis Laseron

Hunter’s assistant in Antarctic science was Charles Francis Laseron. Laseron was educated in Lithgow, then at St. Andrew’s Cathedral Choir School as scholar and chorister. No doubt his singing skills accompanying the gramophone were appreciated when entertainment was required, along with the vocal skills of Hunter, Hurley, and Correll. ‘The Washerwoman’s Secret’, an opera composed by Laseron, was the cause of much raucous laughter.

Laseron’s father could not afford university fees, so Laseron obtained a diploma in geology from Sydney Technical College, while working as a college lecturer. On graduation he became a collector with the Sydney Technological Museum (now the Powerhouse Museum), obtaining leave when joining Mawson’s expedition, and to serve in World War 1. While in Antarctica his work was to obtain, prepare and preserve biological specimens.

Laseron, Hunter and Herbert Murphy’s sledging journey provided support for Edward (‘Robert’) Bage’s Southern Sledging Party. Achievements from their trek included the collection of specimens of granites and gneisses, and discovering nests of the silver grey petrel. Laseron’s second sledging journey examined the coast east of Commonwealth Bay with Frank Stillwell and John Close. Laseron collected eggs, skins and took photographs, and the team were successful in completing their allocated survey work, specimen collection and data collection. Having endured the perils of nature, it was a man-made hazard that almost claimed their lives — the men received carbon monoxide poisoning from their stove while cooking breakfast in a dug-out snow shelter. Laseron’s Antarctic experiences were published in 1947 in South with Mawson.

Like many from Mawson’s expedition, Laseron joined the Australian Imperial Forces. After 2 weeks on the Gallipoli Peninsula he was wounded in the right foot and ankle by a sniper’s bullet. Although physically recovered in three months, Laseron was diagnosed with neurasthenia, and discharged on medical grounds. His wartime experiences were published as From Australia to the Dardanelles, and he wrote many newspaper articles. In World War 2, Laseron’s contribution was as an instructor in map reading and topography – presumably he honed these skills in Antarctica. In this capacity he patented the invention Improved sun compass.

Laseron contributed to the geology and art collections of the Sydney Technological Museum. His interest in geology preceded the AAE; he had published a paper on the Shoalhaven district (1906), and geology and palaeontology papers. As manager of the museum’s art collections, Laseron published Descriptive guide to the collection of old pottery and porcelain, and was largely responsible for the creation of the New South Wales Applied Art Trust. He resigned in 1929 after a lengthy dispute with the museum curator, Arthur Penfold. Laseron established an antiques business, and auctioned books, coins and stamps, becoming a highly respected authority on philately.

In later life Laseron was a clerk for the Colonial Sugar Refinery Company, while continuing to write. His 6 publications on Australian malacology (the study of molluscs) are kept in the Australian Museum, Sydney. He completed 20 essays and over 2,000 drawings and described hundreds of new species, making him a pioneer in this field. A new genera and species of molluscs have been named after him. He was an honorary correspondent of the Australian Museum and in 1952 the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales made him a fellow. His books, The Face of Australia (1953) and Ancient Australia (1954), were well reviewed in the Sydney Morning Herald and The Argus for making the beauty of the Australian landscape of scientific interest to lay readers.

Laseron wrote the 1958 obituary for Sir Douglas Mawson in the Australian Journal of Science, his own obituary appearing in that journal the following year. He was recognised as a scholar of note in the scientific community and was described as having led a full life, much loved by his wife, Mary Theodora Mason, and their 2 children.

Walter Henry Hannam

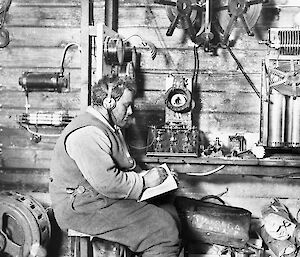

Like Laseron, Hannam lacked a university education – he obtained his science diploma from the Technical College in Sydney and worked as a gas and hydraulic engineer in his father’s business, Hannam & Company. Appointed to the AAE as wireless operator and mechanic, Hannam established the wireless telegraphic system on Macquarie Island and on Mawson’s Antarctic base. Although the wireless masts were ready in early October 1912 and Hannam managed to send a message to Sawyer on Macquarie Island, a mast was destroyed by 322 km/h winds on October 13, causing further delays. Hannam created the foundations for the first radio communications from Antarctica, and his successor, Jeffryes, established reliable two-way messages.

Hannam had an enquiring and inventive mind. While establishing the Macquarie Island base the Aurora lost an anchor, so Gillies (the Aurora’s Chief Engineer) and Hannam designed and constructed a replacement. The Main Base expeditioners conceived, and Hannam created, the gauge with which they measured snow drift. His continued ingenuity in civilian life was probably inspired by his cold Antarctic experiences, including his patent Improvements in rapid type electric water heaters for bath and other domestic service.

Hannam and Francis Bickerton were responsible for preparing the midwinter feast. Fortunately, by this stage in the expedition, Hannam’s repertoire of dishes extended beyond the stew, biscuits and cocoa that comprised his culinary knowledge at the expedition’s outset. Hannam continued work at the hut during the sledging season, as magnetician and general handyman. The 3 islands in the eastern part of Commonwealth Bay were named Hannam Islands by Mawson, in appreciation of Hannam’s valuable contribution to the expedition. The Australian Antarctic Division’s Walter Hannam Building also honours him.

During World War 1, Hannam served in England as a Lieutenant with the Australian Motor Transport Corps, and in France as Corporal with the Australian Wireless Section. His medals included the Star, Victory, and General Service medals. He was discharged due to arthritis in his knees.

Hannam established his own electrical and mechanical engineering business in Mosman, where he lived with his wife. He continued to be passionate about wireless communications and was a founding member of the Wireless Institute of Australia. Hannam is described as being hard working, obliging and persistent. His warm and friendly personality was valued by Mawson, and an asset to the expedition.

Mawson’s Men

Mawson received a knighthood for his achievements, while the efforts of members of the land parties were rewarded with the Kings Silver Antarctic Medal. They had survived Antarctica, the land with the lowest mean temperature and the highest wind velocity on earth.

Most men chosen by Mawson exceeded his expectations in being hardy, amicable and reliable. Personal attributes common to Jones, Hunter, Laseron, Hannam and McLean included being inventive, courageous, optimistic and generous. They were diligent in their work and highly committed to their field of expertise. Although each man made important and unique individual contributions during, and post, their Antarctic experiences, they were proud to be labelled by The Argus as ‘Mawson’s Men’.

Further reading

This article was prepared from a variety of primary and secondary sources including:

- Archibald Lang McLean. Sydney Medical School Online Museum and Archive (2006).

- John George Hunter (1888–1964). Australian Dictionary of Biography Vol 14 (1996).

- Charles Francis Laseron (Carl) (1887–1959). Australian Dictionary of Biography Vol 9 (1983).

- Peter Reynolds, ‘Broughton Hall Psychiatric Clinic’, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008.

- Australian Imperial Force, service records of McLean, Hunter, Laseron and Hannam.