From the outset, the Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–14 (AAE) was recognized by Antarctic historians as an important expedition. In 1928 J. Gordon Hayes wrote: ‘Sir Douglas Mawson’s expedition, judged by the magnitude both of its scale and of its achievements, was the greatest and most consummate expedition that ever sailed for Antarctica’. Considering publication of the AAE Scientific Reports continued until 1947, this is high praise. Medical reports and comment, appearing as appendices in The Home of the Blizzard (1915), and the 1919 AAE Scientific Report Bacteriological and other Researches bear testimony to the lesser known achievements in human studies and medicine. As a plethora of meetings, books, lectures and events celebrate the centenary of AAE, it is timely to review 100 years of Australian Antarctic medicine from the inaugural practice on AAE by its three doctors, McLean, Jones and Whetter.

Mawson had wintered with Shackleton’s British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09 (BAE), and this experience may have influenced his attitude to selection of expedition staff, especially doctors. As Mawson stated: ‘In no department can a leader spend time more profitably than…selection…for a polar campaign the great desideratum is tempered youth.’

BAE had two competent doctors, Marshall and Mackay, both with strong and difficult personalities. Marshall had clashed with Mawson, and twice Shackleton had threatened to shoot Mackay. Mawson was with both doctors on the first ascent of Mount Erebus, and had travelled with Mackay and Edgeworth David over 2000km in 122 days to the vicinity of the South Magnetic Pole. Marshall was navigator and cartographer with Shackleton when they got to within 180km of the South Pole. The first two doctors chosen for AAE could not have contrasted more with those on BAE.

Archibald Lang McLean and Sydney Evan Jones graduated from the University of Sydney in 1910. McLean was 25, had completed a BA (Hons) in French four years earlier, and while a Resident at Lewisham and Coast hospitals in 1911, completed his ChM (Master of Surgery). Jones was two years younger and was a Resident Medical Officer at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in 1911.As Chief Medical Officer of the Main Base at Cape Denison, McLean carried out his medical duties well and performed significant bacteriological and human physiological studies, leading to the award of an MD (Doctor of Medicine) in 1917. He was affectionately known by the group as ‘Dad’. In 1979 the last survivor of the Main Base group, Eric Webb, remembered McLean as an ‘industrious collector of blood samples and something of a father-confessor to all’. McLean stayed a second year and nursed Mawson back to health after his epic journey as well as continuing biological studies and editing The Adélie Blizzard, an AAE newspaper. Jones was a most effective Medical Officer at the Western Base on the Shackleton Ice Shelf. He was unable to complete the bacteriological research due to contamination of the culture media, but was involved in sledging trips. This included leading an 11 week, 330km trip to Gaussberg.

Mawson originally planned for three bases and found difficulty in recruiting a third doctor. Leslie Hatton Whetter, a 1910 graduate from the University of Otago, New Zealand, was a late recruit. AAE records state he was 29 but recent family research suggests he inflated his age by five years. Given ice conditions and the potential for delays in establishing bases at three sites, two days before landing at Cape Denison Mawson combined two groups and named Whetter as Surgeon at Main Base, a role subsidiary to McLean. Whetter’s only recorded medical work was giving a chloroform anaesthetic to the dog Caruso. Although he helped with meteorological observations and was a member of successful sledging parties, he was essentially the ‘collector of ice’, which he did badly. His nickname was ‘Error’. Continual clashes with Mawson led the leader to record in his diary that ‘Whetter is not fit for a polar expedition. I wish I had minded his mother’s cablegram warning me.’ Webb, a fellow New Zealander, suggested ‘Whetter, having been recruited for an independent role as MO of a third wintering party, always felt a bit odd, in which being a New Zealander amongst Australians may have shaded his thinking.’The doctors’ post-expedition careers reflected their life and work on AAE. McLean completed his MD, edited The Home of the Blizzard for Mawson, saw military service in WWI and was awarded a Military Cross. Gassed several times in France, he died prematurely of tuberculosis in 1922. Tributes to him revealed a popular doctor with qualities that were very rare. Laseron, who was also on AAE, wrote ‘Dad, to have known you is enough to have made life worth while…’ Jones specialized in psychiatry and founded the first psychiatric clinic for voluntary patients in Sydney, becoming its superintendent, creating a garden and zoo in the grounds for the patients’ therapy, and was a pioneer in the treatment of mental illness in Australia. On his time in Antarctica he was always reticent. Whetter served in the Great War with the New Zealand Medical Corps, was a doctor in Samoa, and from 1923 practised medicine in a ‘semi-retired way’ in an isolated community at Matakana, New Zealand. He and his wife were very private people and established an extensive, showpiece garden on a large property, although locals regarded him as an eccentric with many hobbies.

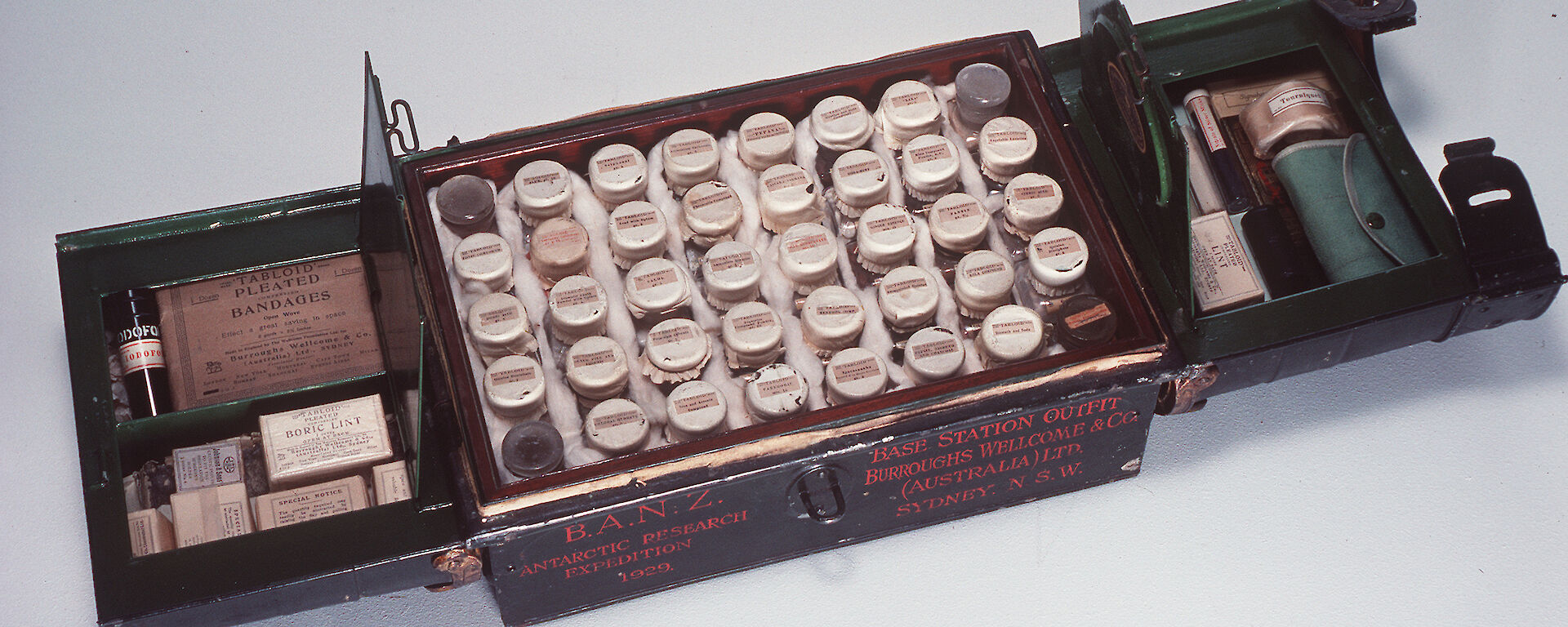

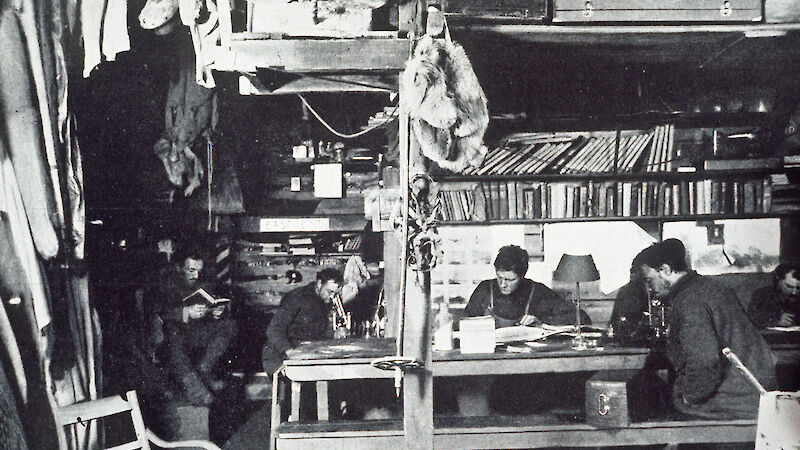

As most indoor activities of the 18 men on AAE had to be performed in 90 sq m of the two huts forming Main Base, there was no dedicated medical area. Fifty five boxes of medical supplies for the voyage, bases and sledging parties, and an additional set of veterinary medicines for the dogs had been loaded on the Aurora in Hobart. Burroughs Wellcome medical chests and Allen and Hanbury surgical instruments, which were supplied to most world-wide expeditions of the era, were the mainstay of AAE. The opening sentences in the medical reports of McLean and Jones — ‘the health of the expedition was remarkably good’ and ‘there was a marked absence of serious illness during the whole period of our stay [Western Base]’ — and the ailments and accidents listed, suggest few medicaments were used. Influenza, skin infections, frostbite, minor casualties during hut building, snowblindness, dysentery, and haemorrhoids were common. The deaths of Ninnis in a fall down a crevasse in December 1912 and Mertz in January 1913, while sledging with Mawson on the Far-Eastern Journey, were serious and tragic. Likewise the psychosis suffered by Jeffries, recruited as wireless operator for the second winter, seriously taxed McLean, the debilitated Mawson, and the rest of the group. It was not until 1969 that Cleland and Southcott considered that the illnesses of Mertz and Mawson were explicable as being due to hypervitaminosis A, from eating husky liver after most other food supplies had been lost. Evidence from assays of husky livers in 1971 and later reviews in 1978 and 1997 give strong support to Cleland’s hypothesis, although we shall never know the truth.

McLean achieved creditable research results despite the primitive conditions in the hut (which had an ambient temperature of 4–7º C), little equipment (slides, spirit lamp, centrifuge, microscope, incubator heated by a kerosene lamp and sterilizer), materials stored under the snow, reagents mislaid for months, overgrowth of media with moulds and lack of availability of subjects. A substantial collection of bacteriological specimens were collected from ice, soil, mud, mammals, birds and fish. Monthly human throat, nose and skin swabs were also collected, together with blood pressures, haemoglobin and cell counts, nail and hair growth, immunological, psychological, dietetic, and general health observations. This first Australian Doctorate for Antarctic medical research was highly rated with the award of a university medal, an editorial in the Medical Journal of Australia, and much comment on its literary style as well as its scientific content.

Mawson’s next Antarctic foray was as Leader of the British, Australian, New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition 1929–31 (BANZARE). Two summer cruises performed extensive research in Antarctic regions and extended geographic discoveries made on the AAE. William Wilson Ingram was Medical Officer and assisted with the biological research. After the expedition he was considered by Mawson as the ideal doctor for such a research undertaking and highly praised, but his medical report was less favourable; three pages of comments on a few medical conditions — influenza, dental, lacerations, minor burns, sprained joints, and prophylactic use of orange juice and milk, with most of the report about a case of scurvy and rickets. This latter case being the cat on board that was initially fed tinned supplies, more latterly fresh meat from the biological specimens, until he recovered completely at Kerguelen, where he obtained his own food from a mouse plague.

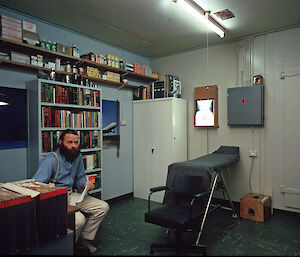

The dramatic changes in technology that have advanced Antarctic logistics and research over the past 100 years have also altered medical practice in the Australian Antarctic program. However, wintering personnel are just as physically isolated today as were Mawson’s groups, albeit for a shorter time, and are subject to the same harsh environment. Those organizing the medical services for the newly established Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (ANARE) in 1947 learned and incorporated much from AAE, much less from BANZARE.

For the first 17 years of ANARE there was no Head Office medical support. From the appointment of a Head Office doctor on the staff of the Australian Antarctic Division in 1963, a highly specialized and efficient Polar Medicine Unit has evolved; not prominent until a well-publicized serious health or medical event occurs. The Unit’s critical functions include recruitment of wintering, field and voyage medical practitioners; medical, dental, laboratory and surgical training; preparation for deployment; provision and maintenance of medical supplies and equipment; and comprehensive medical and dental screening of those going to Antarctica. As McLean found, the close nexus between health care and research has led to the Australian Antarctic Division conducting a comprehensive, multidisciplinary research program in human biology and medicine over decades, with the award of a number of doctorates. Collaboration between the Antarctic Division and many centres of research, both in Australia and overseas, has maintained high standards of research and many publications in peer-reviewed journals.The introduction to McLean’s thesis is an important document for all those contemplating or planning medical research in Antarctica. The pitfalls of such research are clear and have been experienced by many doctors over the past 60 years. McLean’s attempts at immunology certainly played a part in a significant Antarctic immunology program being performed over 30 years, some 60 years after AAE. Personnel in Antarctica have an altered immune response, although no specific disease states have been found. Despite the altered immunity, research on Australian stations has shown that personnel are still able to produce antibodies to specific antigens, an important fact should influenza or other infectious diseases get to Antarctica.

McLean observed a marked slowing down of finger-nail growth on AAE. Donovan repeated this experiment in 1975 at Davis and found no slowing, suggesting modern polar technology lessened the effects of environmental extremes on human physiology. Further work by Gormly and Ledingham confirmed the 1975 study but found a high rate of toe-nail growth, which they attributed to the hot-house environment of modern insulated footwear. Repeated studies are often necessary. Vitamin D research in 1991 showed no lack of Vitamin D. More sophisticated work 15 years later showed Vitamin D supplementation necessary. Similarly, photobiological research on UV in the 1980s suggested UV was not a problem to those working in Antarctica and using protection, but more recent studies showed expeditioners are subject to much greater UV levels.Mawson had difficulty in recruiting doctors for the AAE and this has been a recurrent problem for the Australian Antarctic Division and its search for ‘super generalists’. The key to the success of Australia’s Antarctic medical support is the appropriately trained, generalist procedural medical practitioner — on station or on ship — who is capable of dealing with a broad spectrum of medical possibilities, from appendicectomy and craniotomy, to treatment of trauma and the diverse range of mind and body ailments in between. The 1976 wintering year saw doctors recruited from South Africa and Switzerland, and for the first time a woman wintered on Macquarie Island as doctor. It was not until 1981 that the first woman wintered at an Australian station on the Antarctic Continent as the Davis doctor. With the increase in female graduates from Australian medical schools, medical recruiting by the Antarctic Division improved. However, the numbers of doctors, both male and female, with suitable skills and willing to spend a winter in Antarctica is still limited, and is the Achilles’ heel of the Australian Antarctic program. Despite this, the increasing standard of health care in Antarctica is in part a reflection of community attitudes and the expectations of groups in Antarctica and their families in Australia, as well as technological advances.

Telemedicine has been used successfully between Australian Antarctic stations and Head Office since the 1960s. The first wireless contact between Antarctica and the rest of the world took place on the AAE, with a wireless station being established at Cape Denison and a relay station on Macquarie Island. However, contact with Australia was very variable. Today, satellite communication links from Antarctica to medical practitioners at the Australian Antarctic Division, who have wintered in Antarctica, and medical and dental specialists around Australia, enable critical e-health support on a store and forward telemedicine basis, via narrow bandwidth networks. This allows telephone consultation and digital transmission of X-rays, ultrasound and clinical images 24 hours a day. In response to changing scientific needs, the Polar Medicine Unit has also designed and used a ‘containerized medical facility’ (in a shipping container) so doctors can deal with life-threatening medical and surgical emergencies on chartered research vessels sailing in Antarctic waters.In the wake of McLean, Jones and Whetter, some 500 medical doctors have joined the Australian Antarctic program and provided a complete medical service in Australia’s most remote medical practice. Today’s doctors are just like those on the AAE, with skills additional to their medical ones. This may be in research fields or a wide array of activities that assist the scientists and support personnel in the isolated groups. Few doctors have not enjoyed their Antarctic sojourns. Most look back on their time on the beautiful, harsh and icy continent of Antarctica, or on the animal rich subantarctic sanctuaries, as stimulating and rewarding. Testimony to this is the number of doctors who return for subsequent expeditions.

DESMOND LUGG¹ and JEFF AYTON²

¹Head Polar Medicine, AAD 1968–2001

²Chief Medical Officer, AAD 2002 — present

Drs Lugg and Ayton are currently writing a book on the centenary of Australian Antarctic medical practice.