Tuesday 2 October

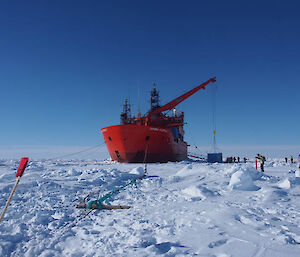

I have a renewed appreciation for the difficult work scientists do in Antarctica after my first brief experience on the ice this week. But it’s not just the scientists who ‘suffer’ for their art, it’s also the team of people supporting them behind the scenes, including the science technical support group and the ship’s crew.

Actually doing science and making progress in your chosen field is time-consuming and often challenging. In Antarctica the time and the challenge is magnified by a biting cold that drains battery power, freezes instrument components that shouldn’t be frozen, numbs fingers and saps strength with every chip of the ice axe or swivel on the ice corer.

I helped sea ice modeller Dr Petra Heil’s team clear about one metre of snow off the ice along a 100m line so that they could then drill 100 holes through the ice, drop a tape measure through each hole and measure the ice thickness and ‘ice draft’ — the amount of ice below the water surface. In some places the ice was more than 3m thick and each hole took 5–10 minutes to drill, depending on whether it was done by hand or with the assistance of a power drill. The sea water that welled up soon began to freeze in the holes and posed a frostbite risk to inappropriately gloved hands.

Other teams out on the ice were sorting out teething problems with their equipment, some of which had never been tested in Antarctica. While most equipment is tested under very cold conditions, it is difficult to fully approximate the combination of snow, ice, seawater and wind that Antarctica delivers, and the effect of these stressors over an extended time. Problems ranged from batteries not working, generators overheating, electronics short-circuiting, seawater freezing in pipes, and computer networks not networking. Many problems also arise with equipment brought from overseas that has different power and connectivity requirements to those available on the ship.

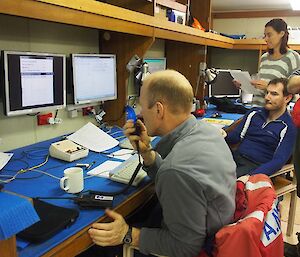

When things go wrong it’s the job of the science technical support team to help make it right. The team of 3 gear officers and 5 electrical, mechanical and software engineers need patience, tolerance, ingenuity and flexibility to cope with the environment (from a rolling ship to a blizzard-blasted, on-ice laboratory) and often stressed or worried scientists whose work in Antarctica could come to an abrupt halt without them.

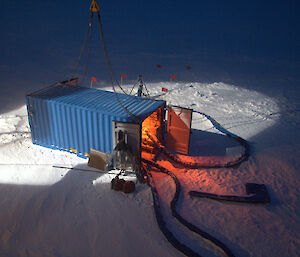

Software and electrical engineer, Michael Field, who is working with the project team operating the Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV), said about 75% of his job involves the design, preparation and testing of equipment, and fixing problems. The team has a shipping container full of parts and equipment to affect robust and safe repairs or modifications, but Michael’s must-have repair kit includes cable ties, side cutters and amalgamating tape.

Members of the team have also been involved in designing and building specialised equipment including the krill light trap used by marine scientist Rob King (see previous blog post) and a video camera system that communicates through the Conductivity, Temperature and Depth (CTD) instrument, to film the light trap in action, 2000–3000m below the ocean surface.

Other behind the scenes responsibilities include engineering, making and installing the vessel’s ice moorings, providing laboratory safety systems and lab usage plans, maintaining and refuelling generators and drills used on the ice, operating the ROV, CTD and underway data collection systems, and providing much of the ship’s emergency response capability. All the data the scientists collect must also be archived for future use, and this weighty task is overseen by data officer Miles Jordan.

While the support team have a small workshop and an instrument room full of computing power, you will generally find them out on the ice fixing problems on the fly. Late into the night, at our second ice station, team members helped Rob King tweak a new pumping system he has deployed to catch krill. By the light of their head torches, and with snow swirling into the shipping container housing the equipment, the team worked without complaint to give Rob’s research the best chance of success.