The report found that, like elsewhere in Australia, climate change is a key driver of change in Antarctica, the sub-Antarctic and the Southern Ocean. Pollution, tourism, commercial fishing, and an expanding human presence, also affect the Antarctic region.

“The Antarctic environment is still in comparatively good condition, but the pressures on the continent and the surrounding ocean are increasing,” Dr Welsford said.

“For example, ice shelves are melting faster due to warming of the upper ocean and lower atmosphere, the human footprint in the region is expanding, and the krill fishery is increasing catches to levels last seen in the 1980s.”

Most importantly, the authors found unequivocal evidence of climate change processes occurring now, which are likely to alter the physical Antarctic environment over the next decades to centuries.

These changes are likely to become irreversible without policy interventions and technological advances.

Antarctic heatwave

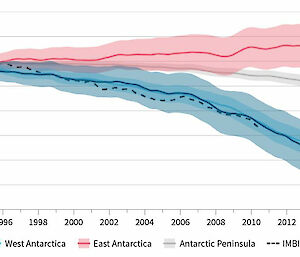

Between 1992 and 2017, global warming caused the loss of almost 2700 gigatonnes (2700 billion tonnes) of ice from the Antarctic ice sheet – including through the collapse of large ice shelves – contributing about 8 mm to mean sea level rise. The speed of this ice loss has quadrupled since the end of the 20th century.

While the Antarctic Peninsula and West Antarctica have experienced the most change, Dr Welsford said recent events suggest that climate change signals are now surfacing in the Australian Antarctic Territory, in East Antarctica – where Australia’s Antarctic stations are located and Australian research efforts are focussed.

In 2019-20, for example, parts of coastal Antarctica, including at Australia’s Casey research station, experienced a three-day heatwave, breaking minimum and maximum temperature records. Casey’s highest maximum of 9.2°C, was 6.9°C higher than the mean maximum temperature for the station over the past 31 years.

“Such extreme temperatures are concerning as these regions are key oases of biodiversity, where plants and animals have adapted over millennia to a specific narrow range of physical conditions,” Dr Welsford said.

Antarctica-Australia links

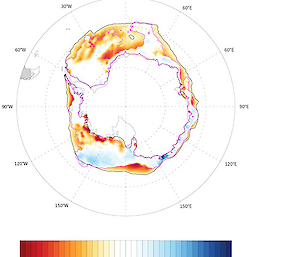

Sea ice extent around the continent has also seen extreme swings recently. Between 1979 and 2018, satellite records showed overall Antarctic sea ice extent increased by about 11,300 square kilometres per year, although there was strong regional and seasonal variation within this trend. But since 2015 sea ice extent has gone into reverse, with a record low in 2016 and another in 2022.

This is significant for Australia as modelling of projected future Antarctic sea ice loss suggests it could increase warming and rainfall changes in Australia’s tropics.

Sea ice reflects the sun’s heat back into space, and sea-ice growth and retreat drives the circulation of huge water masses in the Southern Ocean that interact with other global ocean currents, affecting weather and climate around the world.

“The weather and climate of Australia feel the influence of the Antarctic region because Antarctica is huge, and because the two continents are geographically close, so we see strong links between causes and effect between phenomena in Australia and Antarctica,” Dr Welsford said.

“So understanding the state of the physical environment in the Antarctic region is important for understanding the future of the Australian environment.”

Risk of extinction

Dr Welsford said climate change may benefit some Antarctic species in the short-term, by expanding the size of ice-free areas available for breeding, or with warmer waters increasing biological productivity in the ocean.

However this gain for some will come at a cost for others, made worse by the threat of non-native species establishing and outcompeting native species, and the loss of natural heritage values.

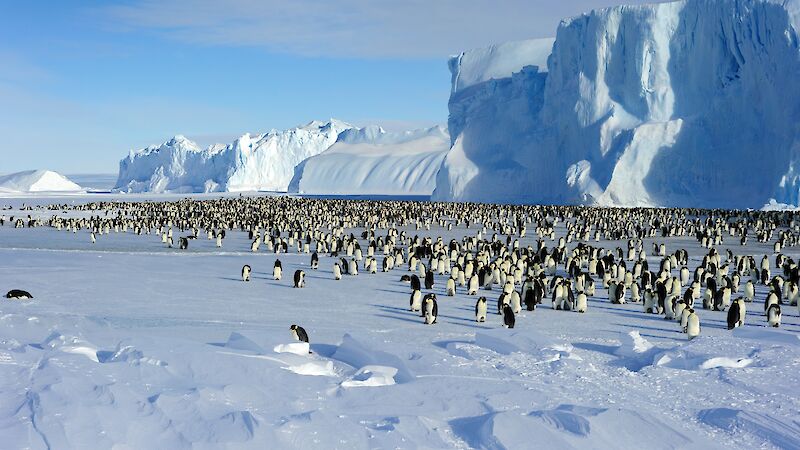

“The rate at which the physical environment is changing appears to be faster than the rate at which Antarctic organisms can adapt, placing some iconic species, such as emperor penguins, at risk of extinction,” he said.

“In our lifetime some species may experience a short-term benefit, but ultimately Antarctica won’t look like it does now, or how Antarctic pioneers like Mawson, Scott and Shackleton experienced it.”

Positive progress

But there are success stories, including the 1989 Montreal Protocol agreement to reduce ozone-depleting gases that create the ozone hole over Antarctica every spring, and contribute to climate change. A full recovery of ozone to 1980 levels is expected by the mid to late 21st century.

The 1991 Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty also provides a comprehensive framework for protection of the Antarctic environment, including a ban on mining and mineral exploration. The Antarctic Treaty Parties have committed to address the effects of climate and environmental change on the Antarctic environment.

Another success is the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), which since 1982 has ensured a sustainably managed krill fishery in the areas of the Southern Ocean it oversees.

Through CCAMLR and the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (both headquartered in Hobart), seabird bycatch in longline fisheries in Antarctic waters is historically low to near zero, thanks to effective research and work with industry.

Clear and present danger

The report authors emphasise that there are still many uncertainties and gaps in the data that limit their ability to anticipate accurately trends and variability over coming decades.

This is largely due to the size and remoteness of the region, the difficulty of access, the challenging nature of Antarctic research, and limited people power.

Despite the uncertainties, the risks associated with climate change are “clear and substantial”.

“The processes that are changing the Antarctic environment are well under way and likely to continue for at least several human lifetimes,” Dr Welsford said.

“While time is running out to do something, to prevent locking in the most extreme changes, I’m optimistic that when the global community comes together, like it has with the Montreal Protocol and other agreements, we can slow and even reverse these changes.”